Animal Models of Acute Exacerbations COPD: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Challenges

by Rika Sari Dewi ★ , Puspita Eka Wuyung , Melva Louisa , Ni Made Dwi Sandhiutami , Irandi Putra Pratomo

Academic editor: Pilli Govindaiah

Sciences of Pharmacy 5(1): 13-21 (2026); https://doi.org/10.58920/sciphar0501482

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International License.

10 Oct 2025

08 Nov 2025

13 Nov 2025

06 Jan 2026

Abstract: Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) represent critical events in disease progression, yet their complex pathophysiology remains incompletely understood. Understanding the mechanisms underlying these exacerbations is essential for developing effective therapeutic strategies and improving patient outcomes. This literature review aims to synthesize current knowledge on the cellular and molecular mechanisms driving acute exacerbations of COPD, highlighting the importance of utilizing appropriate animal models for future research. This review identified rodent models, particularly mice (C57BL/6 strain) and rats (Sprague-Dawley) are predominantly employed due to their genetic tractability and physiological relevance, with occasional use of guinea pigs for airway hyperresponsiveness studies. Combined approaches using cigarette smoke exposure followed by inflammatory triggers (LPS, viral infections) showed the highest translational relevance. Key pathophysiological mechanisms studied include neutrophilic inflammation, oxidative stress, airway remodelling, and mucus hypersecretion. Current animal models provide valuable insight into AECOPD pathophysiology but face limitations in fully recapitulating human disease complexity. Future directions should focus on incorporating comorbidities, aging, and standardized outcome measures.

Keywords: AECOPDAnimal modelsInflammation

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) ranks as the third leading cause of death globally, with acute exacerbations driving irreversible lung function decline, increased mortality, and substantial healthcare burdens (1, 2). These exacerbations accelerate disease progression, reduce quality of life, and impose substantial economic burden on healthcare systems (1, 3). Despite their clinical significance, the molecular and cellular mechanisms orchestrating AECOPD remain enigmatic, hindered by the disease’s heterogeneity and the dynamic interplay between environmental triggers (e.g., pathogens, pollutants) and host responses (4).

AECOPD involves various molecular mechanisms, including inflammatory factors and oxidative stress with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8, and increased free radical production contributing to lung tissue damage (5). Data from the American Thoracic Society shows that AECOPD leads to an increased risk of mortality in the 6-month period following an exacerbation (6). Research in mouse models suggests that Nrf2 inhibition increases susceptibility to emphysema development following cigarette smoke exposure (7). Kubo et al. found that Nrf2 expression decreased in mice exposed to cigarette smoke, but treatment with astaxanthin successfully restored Nrf2 levels and alleviated emphysema symptoms (8). Pasini et al. observed increased expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 in the blood of COPD patients, despite a decrease in FEV1 (9). Nrf2 activators are known to increase the expression of other antioxidant genes such as SOD1 and TXNRD1 in COPD patients, highlighting the importance of Nrf2 in reducing emphysema exacerbations and inflammation due to inadequate responses to oxidative stress (10). In addition, AGEs and RAGE have significant roles in the pathogenesis of COPD (11). Increased expression of AGEs and RAGE has been observed in COPD patients. Gopal et al. found that sRAGE levels were lower in COPD patients and negatively correlated with FEV1 (12). Hoonhorst et al. identified that sRAGE expression was lowest in the plasma of COPD patients, while mRAGE expression was increased (13). Ferhani et al. reported elevated HMGB1 levels in COPD patients, with mRAGE overexpression in airway epithelium and smooth muscle (14). Exposure to cigarette smoke extract induces RAGE-DAMP signaling in the alveolus, triggering inflammatory mechanisms and oxidative stress through activation of the MAPK pathway (15). This increases JNK and p38 activity, which contributes to bronchial epithelial cell damage and chronic inflammation. Increased ERK expression in COPD patients also triggers endothelial cell apoptosis, increased MMP-1, and Mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), resulting in alveolar wall damage and inflammation (16-18). Therefore, increasing sRAGE levels or inhibiting mRAGE are considered potential targets for the prevention and treatment of COPD (19-21).

Animal models play a crucial role in advancing our understanding of AECOPD pathophysiology and testing potential therapeutic interventions. However, the diversity of modelling approaches and the complexity of translating findings to human disease necessitate a comprehensive systematic review to evaluate current methodologies and identify optimal approaches for future research (22). Animal exacerbation models use baseline COPD induction (smoke, elastase, genetic) followed by acute triggers (LPS, bacteria, viruses) to recreate acute‑on‑chronic events (20, 23-25). These models revealed neutrophil‑driven injury, protease activation, impaired antiviral responses, and key inflammatory pathways but face translational gaps in fidelity, endpoints, and heterogeneity (25). These translational challenges necessitate a critical evaluation of existing models and the incorporation of diverse methodologies to enhance the relevance of findings in clinical settings. This review aims to systematically assess the strengths and limitations of current AECOPD animal models, evaluate their translational value in elucidating human disease mechanisms, and propose strategies for optimizing model selection and design to bridge the gap between preclinical research and clinical outcomes, with particular emphasis on integrating biological diversity to reflect patient heterogeneity.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

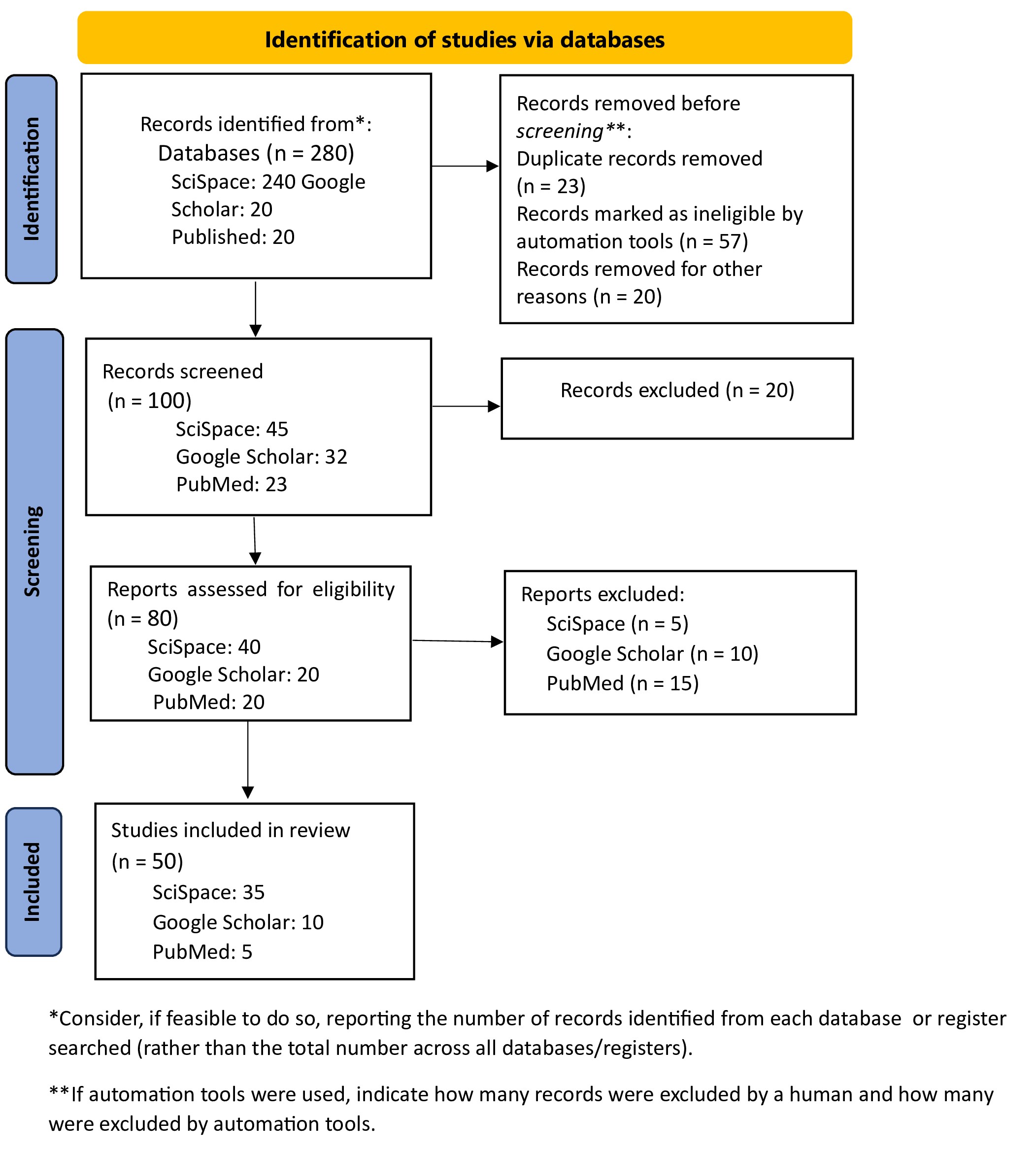

This review was executed through an extensive search of the literature and the careful selection of pertinent studies concerning various animal models used in AECOPD research, focusing on their strengths, limitations, and the implications for future studies in understanding disease mechanisms. A comprehensive systematic literature search adhering to PRISMA guidelines was conducted across SciSpace (240 papers), Google Scholar (20 papers), and PubMed (20 papers), total 280 papers for initial analysis, with studies included only if they utilized animal models for COPD exacerbation research, were published in peer-reviewed journals between 2015–2025, described experimental induction methods for COPD or acute exacerbations, and reported pathophysiological mechanisms or therapeutic interventions; subsequently, data were systematically extracted on animal species/strains, COPD/exacerbation induction protocols, pathophysiological mechanisms, biomarkers, outcome measures, therapeutic interventions, and study limitations/translational relevance.

Results and Discussion

The comprehensive database search yielded a total of 280 potentially relevant articles across all searched databases. After the removal of duplicate records, the remaining studies were systematically screened based on their titles and abstracts to evaluate their relevance to the research objectives and predefined research questions. Studies that met the initial screening criteria were subsequently subjected to full-text assessment using clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This evaluation led to the exclusion of articles that did not meet the required methodological rigor, employed inappropriate or insufficient study designs, or fell outside the thematic scope of the review. Ultimately, 50 studies satisfied all eligibility criteriaand were included in the final qualitative analysis. This rigorous and structured selection process ensured that only high-quality and relevant studies contributed to the synthesis of findings, thereby enhancing the robustness and reliability of the review outcomes. The entire study selection procedure was transparently documented and visualized using a PRISMA flow diagram Figure 1, which clearly illustrates each stage of the review process, including identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of studies.

Animal Species and Models Used

Animal Species

The review revealed that mice and rats are the predominant species used in AECOPD research, largely due to their genetic tractability, ease of handling, cost-effectiveness, and the wide availability of well-established experimental protocols. These characteristics make them particularly suitable for mechanistic studies and genetic manipulations aimed at elucidating disease pathways. In addition, the extensive availability of transgenic and knockout strains allows researchers to investigate specific molecular targets and inflammatory pathways involved in acute exacerbations with a high degree of experimental control. Guinea pigs are used less frequently; however, they provide distinct advantages for investigations focused on airway physiology and pharmacological responsiveness, as their respiratory anatomy and bronchoconstrictive responses more closely resemble those of humans. This similarity is especially relevant for studies evaluating bronchodilators, airway hyperresponsiveness, and mucociliary function, where anatomical and functional comparability to humans is critical. Consequently, although rodent models dominate AECOPD research, the selective use of guinea pigs remains valuable for specific research objectives requiring enhanced translational relevance, particularly for translational airway pharmacology (26, 27), as shown in Table 1.

Species | Common Strains | Primary Applications | Advantages | References |

Mouse | C57BL/6, BALB/c | Genetic manipulation, immunophenotyping, short-term exacerbation models | Genetic tools available, cost -effective, well characterized immune responses | |

Rat | Wistar, Sprague-Dawley | Chronic exposure models, mucus studies, airway physiology | Larger airways, better for physiological measurements | |

Guinea pig | Dunkin-Hartley | Airway responsiveness, pharmacological studies | Similar airway anatomy to humans, good for bronchospasm studies |

Models Used

Evidence-based reviews identify substantial variability in experimental protocols across studies, including inconsistencies in exposure duration, disease induction methods, and outcome measurements. In addition, reporting of key biological variables such as animal sex, strain, and functional endpoints is often incomplete or inconsistent. Most studies predominantly utilize male animals, which represents a significant limitation in translational relevance, as it fails to account for known sex-specific differences in immune responses, airway physiology, and disease progression. This sex bias may limit the generalizability of preclinical findings to the broader patient population and underscores the need for more standardized experimental designs and inclusive reporting practices to enhance reproducibility and clinical applicability in AECOPD research (26, 27).

Methods for Inducing COPD and Acute Exacerbations

The systematic analysis revealed that combined experimental approaches involving chronic cigarette smoke exposure followed by the administration of inflammatory triggers represent the most clinically relevant models for studying acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). These models closely mimic the multifactorial pathophysiology observed in human AECOPD, where long-term exposure to cigarette smoke establishes a persistent inflammatory milieu and induces progressive structural alterations within the airways. This chronic pathological baseline is subsequently intensified by secondary insults, such as bacterial components, viral mimetics, or other pro-inflammatory stimuli, resulting in acute deterioration that parallels clinical exacerbation episodes in patients. Compared with single-factor models, combined approaches more effectively reproduce hallmark clinical and pathological features of AECOPD, including pronounced neutrophilic inflammation, excessive mucus hypersecretion, airway wall remodeling, and reduced responsiveness to corticosteroid therapy. The interaction between chronic smoke-induced injury and superimposed inflammatory challenges enables these models to capture the dynamic nature of exacerbation events, rather than isolated or transient inflammatory responses. Consequently, combined exposure models provide a more robust and translationally relevant framework for investigating disease mechanisms and evaluating therapeutic interventions under conditions that more closely reflect human AECOPD. Building on these findings, the systematic review establishes clear protocol selection guidelines for modeling distinct aspects of COPD pathophysiology, emphasizing model-specific advantages and clinical applicability. For investigations focused on stable COPD phenotypes, prolonged cigarette smoke exposure over a period of approximately 2–6 months remains the gold standard. This duration allows for the gradual development of emphysema, airway remodeling, and persistent low-grade inflammation, thereby replicating the progressive nature of human COPD. Such models are particularly effective in capturing smoking-related oxidative stress pathways and cellular senescence processes that contribute to chronic disease deterioration. In contrast, studies aimed at elucidating acute exacerbations (AECOPD) should preferentially employ combined models that first establish COPD-like pathology through chronic cigarette smoke exposure or elastase preconditioning, followed by the application of acute inflammatory triggers. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is commonly used to mimic bacterial infections, while viral challenges simulate frequent viral precipitants of exacerbations. These two-phase models effectively reproduce the clinical scenario of acute-on-chronic deterioration observed in patients with COPD, demonstrating synergistic inflammatory responses that closely resemble human disease pathology. Notably, combined cigarette smoke and LPS (CS+LPS) models exhibit markedly amplified production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly interleukin-1β (IL-1β), reflecting heightened innate immune activation during bacterial-driven exacerbations. Similarly, elastase-plus-virus systems induce enhanced interferon-mediated signaling, mirroring viral-associated exacerbations characterized by robust antiviral responses and exacerbated airway inflammation. Collectively, these synergistic inflammatory patterns underscore the translational relevance of combined exposure models in capturing the complex immunopathological mechanisms underlying human AECOPD and provide a valuable platform for evaluating targeted therapeutic strategies. For mechanistic studies requiring rapid and standardized outcomes, single elastase administration followed by viral challenge offers distinct experimental advantages, enabling precise temporal analysis of acute-phase responses such as mucus hypersecretion regulation and oxidative burst dynamics within compressed timelines. Accordingly, the review emphasizes that model selection must be closely aligned with specific research objectives: CS+LPS combinations demonstrate the highest predictive value for anti-inflammatory drug development, viral challenge models are optimal for dissecting immune response mechanisms, and acute elastase-based systems facilitate high-throughput screening and pathway-focused investigations. These protocol selection principles, summarized in Table 2, address the critical need for standardized yet flexible approaches that balance biological fidelity with experimental practicality in AECOPD research (29, 30).

Method | Protocol details | Exacerbation model | Clinical relevance | Observed Human Phenotype Replicated | Ref |

Cigarette Smoke (CS) | Nose-only or whole-body exposure, 2-6 months | Limited alone | Produces emphysema and remodelling but lacks acute inflammatory features |

| (27) |

CS + LPS | Chronic CS + intratracheal LPS | Excellent | Reproduces neutrophilic inflammation and mucus hypersecretion seen in bacterial exacerbations |

| (26) |

Elastase/PPE | Single or multiple intratracheal doses | Good when combined | Rapid emphysema induction, useful for viral exacerbation models |

| |

Viral Models | Influenza, rhinovirus, poly(I:C) on COPD background | Excellent | Reproduces viral-triggered exacerbations with appropriate immune responses |

| |

PPE + LPS | PPE-induced COPD + LPS trigger | Good | Useful for metabolic and biomarker studies |

| (30) |

Pathophysiological Mechanisms Studied

This review reveals critical insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD), with animal models serving as indispensable tools for unraveling disease complexity. Three interconnected pathological axes emerge as central to exacerbation biology, each validated across multiple experimental systems.

Inflammatory dysregulation is central to AECOPD pathophysiology. Neutrophilic inflammation, consistently reproduced in CS+LPS and viral challenge models, drives exacerbations through chemokine-mediated recruitment (33). Elevated CXCL1 and CXCL2 levels in BALF correlate with neutrophil infiltration severity, closely reflecting human exacerbations (26, 34). Parallel studies further identify NLRP3 inflammasome activation as a key inflammatory amplifier via IL-1β and IL-18–driven self-perpetuating cycles of tissue damage (35-37). Macrophage polarization shifts further compound this dysregulation, where the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype dominates during exacerbations, only rebalancing toward reparative M2 polarization during recovery phases (38, 39). These findings collectively position inflammation as both initiator and perpetuator of exacerbation events (27, 35).

Oxidative Stress Imbalance emerges as a critical secondary mechanism exacerbating tissue injury. Chronic smoke exposure models demonstrate sustained reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction that overwhelms endogenous antioxidant defenses (15, 40). Depletion of glutathione reserves and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity during exacerbations creates a pro-oxidant milieu that damages airway epithelium and alveolar structures (41). Mitochondrial dysfunction, observed across multiple model systems, exacerbates this imbalance by impairing cellular energy metabolism while generating additional oxidative byproducts (42). This oxidative-antioxidant disequilibrium not only amplifies inflammatory responses but also directly contributes to the accelerated lung function decline characteristic of severe exacerbations (27, 30).

Structural airway alterations complete the pathophysiological triad, with animal models demonstrating persistent remodeling processes that intensify during acute exacerbations. Notably, CS+LPS models exhibit goblet cell hyperplasia patterns comparable to those observed in human autopsy specimens, underscoring their translational relevance. These changes are accompanied by MUC5AC-driven mucus hypersecretion, leading to excessive mucus accumulation and mechanical airway obstruction that contributes to airflow limitation during exacerbations (16, 43-45). Concurrent extracellular matrix changes (particularly collagen deposition and elastin degradation) create irreversible architectural changes that compound functional impairment. These structural modifications, while developing over chronic exposure periods, undergo acute acceleration during exacerbation events, suggesting a "second hit" mechanism where inflammatory and oxidative stressors potentiate remodeling processes (44, 46, 47).

The integration of these mechanisms through animal models has enabled researchers to dissect their temporal relationships and therapeutic vulnerabilities. The NLRP3 inflammasome emerges as a nodal point connecting inflammation and oxidative stress, while MUC5AC regulation bridges structural changes with inflammatory signaling (16, 36, 37, 48). These insights not only explain clinical exacerbation features but also identify biomarkers and therapeutic targets currently under clinical investigation.

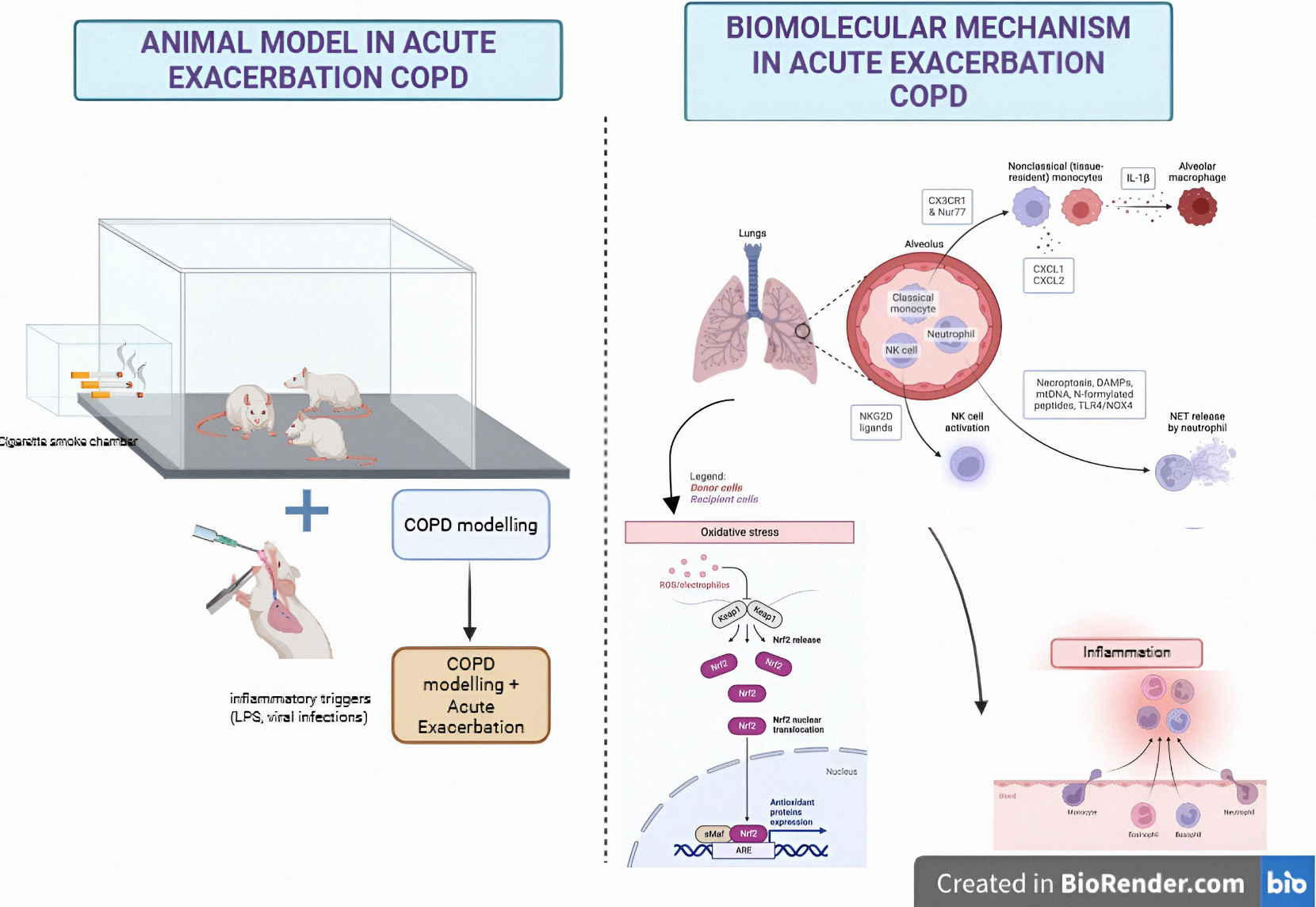

As depicted on Figure 2, animal models of AECOPD are constructed through a two-phase experimental paradigm. The chronic phase involves prolonged exposure of rodents to cigarette smoke or proteolytic enzymes (e.g., elastase) to recapitulate pathophysiological hallmarks of COPD, including emphysematous alveolar destruction and airway remodeling. Subsequently, the acute exacerbation phase is induced via secondary insults such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration or viral challenges, simulating clinical exacerbation scenarios. Mechanistically, these models elucidate corticosteroid resistance exacerbated by Nur77 and EXEL1 signaling, tissue degradation mediated byelastase-like cleavage enzymes, and NKG2D receptor-driven immune activation. Central to exacerbation pathogenesis is the NLRP3 inflammasome, activated by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), extracellular nucleotides (e.g., ATP), and crystalline particulates, which synergistically propagate neutrophilic inflammation and oxidative stress through superoxide dismutase (SOD)/thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) axis dysregulation. These preclinical systems identify interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and redox imbalance as actionable therapeutic targets, underscoring their translational relevance in bridging preclinical insights to human AECOPD pathophysiology.

Inflammatory Biomarkers

The identification of inflammatory biomarkers has revolutionized our understanding of AECOPD progression and therapeutic monitoring. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BALF) analysis remains the gold standard for localized inflammation assessment, with neutrophil percentage serving as a critical real-time indicator of exacerbation severity (49-51). Elevated levels of IL-1β and IL-8 in BALF correlate strongly with neutrophilic airway infiltration, providing mechanistic insights into chemotactic signaling (52). Systemic inflammation is captured through serum biomarkers like CRP and fibrinogen, which reflect the spillover of pulmonary inflammation into circulation. Advanced metabolomic profiling reveals exacerbation-specific energy metabolism disruptions, particularly in fatty acid oxidation pathways, while proteomic studies identify unique protein signatures associated with tissue repair and immune activation (30, 53). At the tissue level, immunohistochemical markers such as NF-κB nuclear translocation and NLRP3 complex formation provide spatial resolution of inflammatory processes, complementing gene expression profiles that map transcriptional networks driving exacerbation biology (35, 53).

Novel Biomarker Discovery

Cutting-edge omics technologies are uncovering multidimensional biomarker panels with diagnostic and prognostic potential. Metabolomic studies in PPE/LPS models demonstrate exacerbation-specific shifts in tryptophan-kynurenine pathways and phospholipid metabolism, suggesting new therapeutic targets for metabolic modulation(30). Transcriptomic analyses via RNA sequencing have identified novel candidate genes like CHI3L1 (chitinase-3-like protein 1), whose expression correlates with mucus hypersecretion and airflow limitation (53). Proteomic profiling reveals dynamic changes in matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity and surfactant protein degradation patterns that could serve as early warning signs for exacerbation onset. These multi-omics approaches enable the construction of exacerbation "fingerprints" that integrate molecular, cellular, and systemic changes into comprehensive biomarker panels.

Therapeutic Interventions

Current therapeutic development leverages three strategic approaches: targeted anti-inflammatory agents, natural compound formulations, and antiviral strategies. NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors like MCC950 show particular promise, reducing IL-1β release by 60-70% in preclinical models while preserving epithelial barrier function (54). The CCR5 antagonist maraviroc demonstrates dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects in influenza-challenged models, reducing viral load by 2 logs and neutrophil infiltration by 40% (55). Traditional medicine compounds exhibit pleiotropic effects, Hochuekkito modulates macrophage polarization, while Lianhua Qingke downregulates MUC5AC expression through STAT6 inhibition (31, 44, 56). Emerging combination therapies pair TLR3 agonists with corticosteroids, achieving synergistic reduction in viral replication (85% inhibition) and inflammation markers (IL-6 reduced by 50%) in rhinovirus models (31, 32, 35).

Model Limitations

Despite their utility, current models face significant translational barriers. Anatomical disparities between rodent and human airways (including dichotomous vs. monopodial branching patterns) fundamentally alter particle deposition and inflammatory cell recruitment (27). The near-exclusive use of young male rodents (90% of studies) ignores aging-related immunosenescence and hormonal influences on disease progression. Methodological inconsistencies create reproducibility challenges, with cigarette smoke exposure durations varying from 4-24 weeks across studies and LPS dosing regimens differing 10-fold between laboratories. Chronic disease modeling remains particularly problematic, as most studies terminate at 8-12 weeks, failing to capture the decades-long progression of human COPD (23, 26, 27).

Translational Relevance

Successful translations highlight the value of carefully designed models. NLRP3 inflammasome activation patterns show remarkable cross-species consistency, with identical caspase-1 cleavage patterns observed in murine and human exacerbation samples (4, 53). Metabolomic signatures of altered arachidonic acid metabolism demonstrate 80% concordance between mouse models and patient sera. However, persistent translational failures underscore systemic challenges - 78% of compounds effective in animal models fail clinical trials due to species-specific pharmacokinetics and divergent disease endotypes. Outcome measure discordance remains problematic, with murine Penh values (airway resistance proxies) showing poor correlation to human FEV1 decline rates.

Discussion and Future Directions

The development of next-generation models for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations necessitates the integration of biological diversity to more accurately reflect clinical heterogeneity. Aging should be modeled using rodents aged 18 to 24 months to replicate the decline in lung function associated with aging, with longitudinal tracking of FEV1 reduction serving as a key metric. It is imperative to prioritize sex-balanced cohorts to investigate the hormonal influences on inflammatory pathways, particularly the regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome mediated by estrogen and the recruitment patterns of neutrophils influenced by testosterone. Protocols for the induction of comorbidities should incorporate both metabolic and cardiovascular components, such as high-fat diets combined with intermittent hypoxia to model obesity-COPD overlap syndrome, as well as angiotensin-induced vascular injury to simulate pulmonary hypertension, thereby capturing the multifactorial interactions of diseases.

Efforts toward standardization must address critical variability in existing methodologies. Chronic models should mandate a minimum of six months of cigarette smoke exposure (at least five cigarettes per day) or standardized doses of porcine pancreatic elastase (ranging from 50 to 75 U/kg), coupled with quarterly microCT validation to assess the progression of emphysema. Exacerbation triggers require precise dosing: LPS at concentrations of 0.5 to 1.0 μg/g for bacterial-type inflammation and calibrated viral titers to ensure consistent interferon responses. Outcome panels should unify core metrics, including percentages of neutrophils in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), oscillometric measurements of airway resistance, and quantification of airspace via microCT, alongside secondary biomarkers such as serum sRAGE levels and sputum metabolomic profiles for multidimensional assessment.

The incorporation of precision medicine approaches is revolutionizing the relevance of these models through advanced genetic and computational strategies. Patient-derived xenograft models utilizing NOG-EXL mice facilitate personalized studies of exacerbation trajectories by engrafting human bronchial epithelial cells from COPD patients. Furthermore, therapeutic development must adopt frameworks for cross-model validation to address the challenges of translational failures. MMP12 inhibitors must demonstrate efficacy in both elastase-induced acute injury models and chronic smoke exposure models. NLRP3 inflammasome blockers should exhibit IL-1β suppression across paradigms involving viral (poly(I:C)) and bacterial (LPS) challenges. Additionally, CXCR2 antagonists require validation in aged models (greater than 20 months) with comorbid atherosclerosis to adequately address the complexities associated with real-world patient populations.

This coordinated approach is poised to transform animal models into predictive platforms for the development of personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately bridging the gap between laboratory discoveries and clinical outcomes in the management of COPD exacerbations.

Recommendations for Protocol Standardization

To address translational limitations in AECOPD research, we propose standardized protocols including a minimum 6-month cigarette smoke exposure to mirror human emphysema timelines, intranasal LPS dosing (0.5–1.0 μg/g ≤72h pre-assay) for bacterial exacerbation modeling, harmonized outcome measures prioritizing airway resistance, BALF neutrophil, and histopathological emphysema scoring, alongside secondary biomarkers like serum sRAGE and NLRP3 activity; comorbidity integration mandates aged models (≥18-month rodents), sex-stratified cohorts, and PM2.5 co-exposure (10 mg/m³, 4h/day) to simulate environmental triggers, complemented by multi-omics validation requiring RNA-seq/LC-MS profiling and ≥80% cross-species biomarker alignment with human datasets.

Conclusion

This systematic review underscores the critical role of animal models in advancing AECOPD research while delineating pathways for future innovation. The combined CS+LPS and elastase+viral challenge models have emerged as gold standards, effectively replicating bacterial and viral exacerbation phenotypes through synergistic inflammatory cascades. Rodent models, despite anatomical limitations, remain indispensable for their genetic tractability and cost-effectiveness, particularly in elucidating neutrophilic inflammation dynamics and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, mechanisms now validated in human trials. While these models have successfully identified therapeutic targets like CCR5 antagonists and metabolomic biomarkers with 70-80% cross-species consistency, translational gaps persist due to inherent biological disparities and methodological variability across laboratories. Moving forward, the field must prioritize standardized protocols (e.g., ≥6-month smoke exposure durations, unified LPS dosing) alongside biologically diversified models incorporating aging, sex differences, and cardiometabolic comorbidities. The integration of multi-omics approaches particularly spatial transcriptomics and longitudinal metabolomics will be crucial for mapping exacerbation trajectories and validating targets across model systems. Clinically, enhanced translational value requires alignment of preclinical endpoints with patient-relevant outcomes, such as combining microCT airspace quantification with FEV1 decline rates. Ultimately, while current models provide an essential scaffold for AECOPD research, their evolving refinement through systems biology approaches and humanized systems will determine the pace of therapeutic breakthroughs for this complex, multifactorial condition. Therefore, we urgently call for the COPD research community prioritize the development of next-generation models that incorporate biological diversity, including aging trajectories, sex-specific pathophysiology, and multimorbidity networks, as essential catalysts for bridging the translational gap and facilitating the delivery of precision therapies for COPD exacerbations.

Abbreviations

AECOPD: Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; BALF: Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid; CCR5: C-C Chemokine Receptor Type 5; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CRP: C-Reactive Protein; CS: Cigarette Smoke; CXCL1: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1; CXCR2: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 2; DAMPs: Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns; ERK: Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase; FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second; IL: Interleukin (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β); JNK: c-Jun N-terminal Kinase; LC-MS: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; MAPK: Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; microCT: micro-Computed Tomography; MMP: Matrix Metalloproteinase (e.g., MMP-1, MMP-12); MUC5AC: Mucin 5AC; NKG2D: Natural Killer Group 2D; NLRP3: NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (inflammasome); Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PM2.5: Particulate Matter ≤2.5 Micrometers; PPE: Porcine Pancreatic Elastase; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RAGE: Receptor for Advanced Glycation End products; SOD: Superoxide Dismutase; STAT6: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 6; TLR3: Toll-Like Receptor 3; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; TXNRD1: Thioredoxin Reductase 1; TXNIP: Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein.

Declarations

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Funding Information

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicting interest.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2025 Report). 2025.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Pocket Guide to COPD: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention. 2025.

- Soriano JB, Kendrick PJ, Paulson KR, Gupta V, Abrams EM, Adedoyin RA, et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):585–96.

- Zhang L, Jia X, Zhang Z, Yu T, Geng Z, Yuan L. Mining potential molecular markers and therapeutic targets of COPD based on transcriptome-sequencing and gene-expression chip. Arch Med Sci. 2024;20(5):e-pub ahead of print.

- Pantazopoulos I, Magounaki K, Kotsiou O, Rouka E, Perlikos F, Kakavas S, et al. Incorporating biomarkers in COPD management: the research keeps going. J Pers Med. 2022;12(1).

- Nici L, Aaron SD, Alexander PE, Au DH, Boyd CM, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):E56–69.

- Iizuka T, Ishii Y, Itoh K, Kiwamoto T, Kimura T, Matsuno Y, et al. Nrf2-deficient mice are highly susceptible to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Genes Cells. 2005;10(12):1113–25.

- Kubo H, Asai K, Kojima K, Sugitani A, Kyomoto Y, Okamoto A, et al. Astaxanthin suppresses cigarette smoke-induced emphysema through Nrf2 activation in mice. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(12):673.

- Fratta Pasini AM, Ferrari M, Stranieri C, Vallerio P, Mozzini C, Garbin U, et al. Nrf2 expression is increased in peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from mild & moderate ex-smoker COPD patients with persistent oxidative stress. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1733–43.

- Ngo V, Duennwald ML. Nrf2 and oxidative stress: a general overview of mechanisms and implications in human disease. Antioxidants. 2022;11(12):2345.

- Reynaert NL, Vanfleteren LEGW, Perkins TN. The AGE-RAGE axis and the pathophysiology of multimorbidity in COPD. J Clin Med. 2023;12(10):3366.

- Gopal P, Reynaert NL, Scheijen JLJM, Schalkwijk CG, Franssen FME, Wouters EFM, et al. Association of plasma sRAGE, but not esRAGE, with lung function impairment in COPD. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):24.

- Hoonhorst SJM, Lo Tam Loi AT, Pouwels SD, Faiz A, Telenga ED, van den Berge M, et al. Advanced glycation end-products and their receptor in different body compartments in COPD. Respir Res. 2016;17(1):46.

- Ferhani N, Letuve S, Kozhich A, Thibaudeau O, Grandsaigne M, Maret M, et al. Expression of high-mobility group box 1 and of receptor for advanced glycation end products in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(9):917–27.

- Addissouky TA, El Sayed IET, Ali MMA, Wang Y, El Baz A, Elarabany N, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation: elucidating mechanisms of smoking-attributable pathology for therapeutic targeting. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2024;48(1):16.

- Deshmukh HS, Case LM, Wesselkamper SC, Borchers MT, Martin LD, Shertzer HG, et al. Metalloproteinases mediate Mucin 5AC expression by epidermal growth factor receptor activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):305–14.

- Zong D, Li J, Cai S, He S, Liu Q, Jiang J, et al. Notch1 regulates endothelial apoptosis via the ERK pathway in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2018;315(3):C330–40.

- Mercer BA, Kolesnikova N, Sonett J, D’Armiento J. Extracellular regulated kinase/mitogen activated protein kinase is up-regulated in pulmonary emphysema and mediates matrix metalloproteinase-1 induction by cigarette smoke. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17690–6.

- Albano GD, Gagliardo RP, Montalbano AM, Profita M. Overview of the mechanisms of oxidative stress: impact in inflammation of the airway diseases. Antioxidants. 2022;11(4):2237.

- Upadhyay P, Wu CW, Pham A, Zeki AA, Royer CM, Kodavanti UP, et al. Animal models and mechanisms of tobacco smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2023;26(7–8):275–305.

- Fang L, Zhang M, Li J, Zhou L, Tamm M, Roth M. Airway smooth muscle cell mitochondria damage and mitophagy in COPD via ERK1/2 MAPK. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(22): 13987.

- Wright JL, Cosio M, Churg A. Animal models of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295(1):L1–15.

- Wright JL, Cosio M, Churg A, Wright JL. Animal models of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L1–15.

- Churg A, Wright JL. Testing drugs in animal models of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(6):550–2.

- Tanner L, Single AB. Animal models reflecting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and related respiratory disorders: translating pre-clinical data into clinical relevance. J Innate Immun. 2020;12(3):203–25.

- Feng T, Cao J, Ma X, Wang X, Guo X, Yan N, et al. Animal models of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11: 1474870.

- Ghorani V, Boskabady MH, Khazdair MR, Kianmeher M. Experimental animal models for COPD: a methodological review. Tob Induc Dis. 2017;15(1):25.

- Lee SY, Cho JH, Cho SS, Bae CS, Kim GY, Park DH. Establishment of a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mouse model based on elapsed time after LPS intranasal instillation. Lab Anim Res. 2018;34(1):1–10.

- Singanayagam A, Glanville N, Walton RP, Aniscenko J, Pearson RM, Pinkerton JW, et al. A short-term mouse model that reproduces the immunopathological features of rhinovirus-induced exacerbation of COPD. Clin Sci. 2015;129(3):245–58.

- Kim HY, Lee HS, Kim IH, Kim Y, Ji M, Oh S, et al. Comprehensive targeted metabolomic study in the lung, plasma, and urine of PPE/LPS-induced COPD mice model. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2748.

- Xiao C, Cheng S, Li R, Wang Y, Zeng D, Jiang H, et al. Isoforskolin alleviates AECOPD by improving pulmonary function and attenuating inflammation through downregulation of Th17/IL-17A and NF-κB/NLRP3. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:1-14.

- Ferrero MR, Garcia CC, Dutra de Almeida M, Torres Braz da Silva J, Bianchi Reis Insuela D, Teixeira Ferreira TP, et al. CCR5 antagonist maraviroc inhibits acute exacerbation of lung inflammation triggered by influenza virus in cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(7):620.

- Margraf A, Lowell CA, Zarbock A. Neutrophils in acute inflammation: current concepts and translational implications. Blood. 2022;139(14):2130–44.

- Komolafe K, Pacurari M. CXC chemokines in the pathogenesis of pulmonary disease and pharmacological relevance. Int J Inflam. 2022;2022:1–16.

- Zhang J, Xu Q, Sun W, Zhou X, Fu D, Mao L. New insights into the role of NLRP3 inflammasome in pathogenesis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:4155–68.

- Paik S, Kim JK, Shin HJ, Park EJ, Kim IS, Jo EK. Updated insights into the molecular networks for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2025;22(6):563–96.

- Xiao S, Lv Y, Ji Y, Dong Y, Liu M, Li T, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a pivotal orchestrator of multisystem diseases—from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic innovation. Mol Biol Rep. 2025;52(1):1026.

- Luo M, Zhao F, Cheng H, Su M, Wang Y. Macrophage polarization: an important role in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15: 1352946.

- Wu S, Zhao S, Hai L, Yang Z, Wang S, Cui D, et al. Macrophage polarization regulates the pathogenesis and progression of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2025;24(7):103820.

- Seo YS, Park JM, Kim JH, Lee MY. Cigarette smoke-induced reactive oxygen species formation: a concise review. Antioxidants. 2023;12(9):1732.

- Gomar S, Bou R, Puertas FJ, Miranda M, Romero FJ, Romero B. Current insights into glutathione depletion in adult septic patients. Antioxidants. 2025;14(9):1033.

- Stańczyk M, Szubart N, Maslanka R, Zadrag-Tecza R. Mitochondrial dysfunctions: genetic and cellular implications revealed by various model organisms. Genes (Basel). 2024;15(9):1153.

- Mori A, Matsumoto R, Ichikawa S, Ishimori K, Ito S. Enhancement of cigarette smoke extract-induced goblet cell metaplasia and hyperplasia exerted through IL-13 receptor α1 expression. Toxicol Lett. 2025;410:177–87.

- Hao Y, Wang T, Hou Y, Wang X, Yin Y, Liu Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of Lianhua Qingke in airway mucus hypersecretion of acute exacerbation of COPD. Chin Med. 2023;18(1):145.

- Wang X, Hao Y, Yin Y, Hou Y, Han N, Liu Y, et al. Lianhua Qingke preserves mucociliary clearance in rats with acute exacerbation of COPD by maintaining ciliated cells proportion and protecting structural integrity and beat function of cilia. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2024;19:403–18.

- Naba A. Mechanisms of assembly and remodelling of the extracellular matrix. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(11):865–85.

- Lu P, Takai K, Weaver VM, Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(12):a005058.

- Pinzón-Fernández MV, Saavedra-Torres JS, López Garzón NA, Pachon-Bueno JS, Tamayo-Giraldo FJ, Rojas Gomez MC, et al. NLRP3 and beyond: inflammasomes as central cellular hub and emerging therapeutic target in inflammation and disease. Front Immunol. 2025;16: 1624770.

- Davidson KR, Ha DM, Schwarz MI, Chan ED. Bronchoalveolar lavage as a diagnostic procedure: a review of known cellular and molecular findings in various lung diseases. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(9):4991–5019.

- Sureka N, Sharan S, Ahluwalia C, Ahuja S, Ranga S. Diagnostic utility of bronchoalveolar lavage in pulmonary disorders. Rev Esp Patol. 2025;58(3):100830.

- Zhang H, Deng D, Li S, Ren J, Huang W, Liu D, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid assessment facilitates precision medicine for lung cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2023;1–22.

- Zareba L, Szymanski J, Homoncik Z, Czystowska-Kuzmicz M. EVs from BALF—mediators of inflammation and potential biomarkers in lung diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(7):3651.

- Wang H, Zhong Y, Li N, Yu M, Zhu L, Wang L, et al. Transcriptomic analysis and validation reveal the pathogenesis and a novel biomarker of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):27.

- Zheng Y, Zhang X, Wang Z, Zhang R, Wei H, Yan X, et al. MCC950 as a promising candidate for blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a review of preclinical research and future directions. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 2024;357(11): e2400459.

- Qi B, Fang Q, Liu S, Hou W, Li J, Huang Y, et al. Advances of CCR5 antagonists: from small molecules to macromolecules. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;208:112819.

- Fukuda K, Matsuzaki H, Hiraishi Y, Miyashita N, Ishii T, Yuki M, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Japanese herbal medicine Hochuekkito in a mouse model of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacology. 2024;109(2):121–6.

ETFLIN

Notification

ETFLIN

Notification