Inhibitory Effect of Herbal Compounds on the Oxygen-Insensitive NADPH Nitro Reductase Enzyme of Metronidazole-Resistant Helicobacter pylori

by Mohammadreza Saeed , Anoosh Eghdami ★

Academic editor: James H. Zothantluanga

Sciences of Phytochemistry 2(1): 77-87 (2023); https://doi.org/10.58920/sciphy02010098

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International License.

03 Apr 2023

23 May 2023

26 May 2023

28 May 2023

Abstract: Helicobacter pylori is a significant risk factor for chronic gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer. The purpose of this article is to investigate the potential impact of fifty herbal compounds derived from Ginger and Parsley plants, known for their antibacterial properties on the Oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme of metronidazole-resistant H. pylori. In the present study, the information on the structure of compounds, the H. pylori resistant to metronidazole enzyme, myristicin, and shogaol derivatives were obtained from databases such as ZINC15, RCSB (Protein Data Bank), and PubChem, respectively. Finally, molecular docking was performed with iGemdock2.1 and Molegro Virtual Docker. After molecular docking, four out of the fifty phytocompounds showed the lowest energy and the highest number of interactions with the amino acids at the binding sites. Among these four phytocompounds, the best phytocompound was N-Vanillyloctanamide derived from Ginger. Our molecular docking study suggests that ginger can be introduced as a potential candidate to inhibit the growth of H. pylori.

Keywords: Helicobacter pyloriHerbal compoundsMetronidazole resistanceMolecular docking

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a significant risk factor for chronic gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer (1). It is a gram-negative, spiral-shaped, flagellated bacterium that has infected almost half of the world's population (2). The annual rate of infection in developing countries ranges from 4% to 15%, while in developed countries, it is only 0.5% (3). H. pylori has developed an acid adaptation mechanism that increases the regulation of periplasmic pH in the harsh acidic environment of the stomach by regulating urease activity (4). Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites evolve over time and no longer respond to medicines, making infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness, and death (5). Treatment of H. pylori infection comprises a combination of antibiotics and acid-reducing proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). The most common antibiotics are metronidazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. The common PPIs include pantoprazole, emiprazole, lansoprazole and rabiprazole. Combined treatments are usually prescribed for 14 days (6). In most regions of the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of H. pylori AMR to metronidazole is more than 15% (7).

Acquisition of resistance is associated with the mutational inactivation of the rdxa gene, which encodes an oxygen-sensitive NADPH nitroreductase. In H. pylori, a mutation in the rdxa gene is significantly associated with metronidazole resistance (8, 9). Studies conducted in Iran have shown that the resistance of H. pylori to the metronidazole antibiotic is very high, at about 57.4%. This resistance is about 46.6% in Asian countries. The highest level of resistance of this microorganism to metronidazole is in African countries, where it reaches 97.55% (3).

Essential oils are a mixture of volatile compounds that are produced as secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. According to the International Organization for Standardization, essential oils are products extracted from plant sources or fruits using steam or water distillation methods. Their chemical compositions are very different based on factors such as the plant, environment, and extraction method. Due to their antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties, essential oils can be a suitable alternative in the food and pharmaceutical industries (10).

The in silico method involves the use of databases, molecular modelling methods, data analysis and mining tools, homology modelling, and pharmacophore modelling (11). An in silico study has shown that new 1,2,3 Oxadiazole derivatives have anti-H. pylori activities (12). In silico analysis has also revealed that Scrophularia striata linalool can eliminate H. pylori (13), and in silico studies have shown that mango ginger is effective against H. pylori (14). In this article, we aim to investigate the potential impact of fifty herbal compounds derived from ginger and parsley plants, known for their antibacterial properties, on the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme of H. pylori that is resistant to metronidazole.

Material and Methods

This research was conducted in a descriptive-analytical manner to study the role of different structural parameters in a set of compounds with antibacterial properties. To investigate the relationship between compounds derived from parsley and ginger plants and the resistance of the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme of H. pylori to metronidazole, we used the Molegro Virtual Docker model 6 software and iGemdock v2.1.

Molecular Docking by Molegro Virtual Docker Software

Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) is an integrated platform for predicting protein-ligand interactions. The software handles all aspects of the docking process, from preparing molecules to determining the potential binding sites of the target protein and predicting the binding modes of the ligands. To use the software, we selected the "import molecules" option from the file section and loaded the 3qdl protein file in pdb format. During loading, we removed water and protein ligands by unchecking the boxes next to them. MVD software is a valuable tool for discovering and identifying new drugs based on accurate optimization methods. The data obtained from MVD software have been more accurate in comparison to other software (15). To perform the docking analysis, we prepared the three-dimensional structure of the desired plant compounds and the receptor using various databases, including PDB, ADMETlab, and ZINC15.

Ligand Preparation

To prepare the ligand, we used ChemBio3D and followed these steps: Firstly, we imported the ligand structure file in a compatible format, such as PDB, MOL, or SDF, into ChemBio3D. Then, we removed any unwanted atoms or molecules from the ligand, such as solvent molecules or counterions, using the "Clean Structure" tool. We added hydrogen atoms to the ligand and assigned appropriate protonation states to ionizable groups based on the pH of the system using the "Protonate" tool. Next, we optimized the ligand geometry and minimized any steric clashes between atoms using the "Minimize Energy" tool. Finally, we saved the ligand structure in a compatible format for further analysis or use in molecular docking studies using the "Save As" tool. Overall, ChemBio3D provided a user-friendly interface for ligand preparation and helped us save time and effort in preparing ligand structures for various applications in chemical and biological research.

Receptor Preparation

Chimera is a popular software tool for molecular modelling and visualization that can also be used for receptor preparation. Here are the general steps to prepare a receptor using Chimera: Firstly, obtain the structure of the receptor from a database such as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate it using a homology modelling tool. Then, clean up the receptor structure by fixing errors or missing atoms using Chimera's built-in tools such as "Add H" and "Repair Structure". Any unwanted molecules in the receptor structure can be removed by selecting them using Chimera's "Select" tool and then deleting the selected molecules. Missing loops in the receptor structure can be added using Chimera's "Model Loop" tool. The receptor structure can be optimized using Chimera's "Minimize Structure" tool, which performs energy minimization to optimize the geometry of the structure. Partial charges can be assigned to the receptor atoms using Chimera's "Add Charge" tool, which is essential for molecular docking and other simulations. Once these steps have been completed, the prepared receptor structure can be saved in a format suitable for further simulations, such as PDB or mol2 format. Overall, Chimera is a powerful tool for receptor preparation and can be used to prepare high-quality receptor models for molecular docking, virtual screening, and other simulations.

In this study, we prepared the three-dimensional structure of the protein 3qdl using the PDB database. To accurately examine the information obtained from the MVD software, access to the exact position of the amino acids involved in the ligand-receptor interaction is necessary, and extensive studies were carried out to access this data using the ligand map section of the MVD software. At the time of preparation, the A chain of 3qdl protein is selected for further steps and docking.

iGemdock software

iGemdock v2.1 is a standalone integrated virtual screening and molecular docking software developed by Jinn-Moon Yang of National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan. This docking software determines the orientation and conformation of the ligand concerning the active site of the protein of interest. Using this software, which is a graphical-automatic system for drug discovery, the integration of docking, screening, post-analysis, and visualization of different ligands can be accomplished. After docking, iGemdock generates protein-ligand interaction profiles of electrostatic (E), hydrogen bonding (H), and van der Waals (V) interactions. In the post-screening analysis, iGemdock infers the pharmacological interactions and clusters the screening compounds based on their interaction profiles and structures. The docked poses were visualized by RasMol. The empirical scoring function of iGemdock was estimated as Energy = vdW+Hbond+Elec. In the present study, we investigated the molecular interaction between the plant compounds, such as parsley and ginger, and the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase using iGemdock version 2.1, a specific molecular docking software. This software allows for three-dimensional observation of the interaction of Myristicin and 6-shogaol, as well as similar compounds, with the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase, a series of amino acids participating in the interaction, and active functional groups on plant molecules. In our study, to minimize errors, all docking conditions for herbal compounds and standard drugs, including the software used, the number of interactions, the interaction study area, the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme under study, and the docking speed, were considered to be the same. We performed molecular docking between the plant compounds and the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase inhibitors using the standard docking method (in which the number of interactions was 70 and the interaction zone diameter was 200 angstroms) with the ability to investigate hydrogen-electrostatic and van der Waals interactions in the entire active site of the enzyme, followed by comparing the results.

Method Validation

Method validation is an essential step in the development and evaluation of computational tools such as iGemdock and MVD. The validation process aims to assess the accuracy, precision, and reliability of the methods used in these tools to ensure that they produce valid and reproducible results.Several studies have been conducted to validate the performance of iGemdock and MVD in predicting protein-ligand interactions. The screening accuracy was generally improved when iGEMDOCK considered the pharmacological interactions. Similarly, another study evaluated MVD's ability to predict binding affinities using a dataset of 109 protein-ligand complexes. The results showed that MVD accurately predicted binding affinities and had a good correlation with experimental data (15, 16). In addition to these studies, the method validation process typically involves several steps, including defining the scope and objectives of the validation study, selecting an appropriate dataset of protein-ligand complexes with known experimental binding affinities, evaluating the accuracy and precision of the tool's predictions using metrics such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and correlation coefficients, assessing the reliability and reproducibility of the tool's predictions, and documenting the validation results in a report or publication. Overall, these studies demonstrate the validity and reliability of iGemdock and MVD in predicting protein-ligand interactions and support their usefulness in drug discovery and development.

To validate the results of MVD and iGemdock simulations, the RMSD was calculated as a measure of the difference between the predicted and reference structures. The RMSD value was calculated separately for both the protein and the ligand. A low RMSD value indicates that the predicted complex structure was in good agreement with the reference structure, suggestive of favorable interactions between the ligand and protein and a predicted binding mode similar to the native binding mode.

Analysis of Docking Results

Biovia Discovery Studio is a commercial-grade graphical visualization tool for viewing, segmenting, analyzing, and modelling data. Firstly, we opened this software and loaded the 3qdl protein PDB file into it. We determined the amino acids of the 3qdl protein binding sites and compared the amino acids of the ligand binding sites with the protein. After performing successive docking to investigate the binding tendency of plant compounds to the receptor, the obtained results were presented in the table. To compare two molecules, Flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and Glycerol (GOL) were studied as control cases.

Binding Site Search

We used this software to identify the amino acids in the binding sites of the 3qdl protein. The amino acids in the binding sites of this protein in all four chains (A, B, C, D) were as follows: Arg16, His17, Ser18, Lys20, Glu34, Pro44, Ser45, Ser46, Asn48, Asn73, Ile142, Cys159, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Gly163, Lys198, and Arg200. The results of docking were examined in two dimensions. The first dimension was the energy of each ligand, and the second dimension was the amino acids in the binding sites of each ligand.

Toxicity Studies

ADMET studies are a crucial aspect of drug discovery and development, as they provide valuable information on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of a drug candidate. The acronym ADMET stands for Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. These five factors are critical in determining the efficacy and safety of a drug. Overall, ADMET studies are essential in optimizing drug development and ensuring that safe and effective drugs are brought to the market. They can be conducted using various in vitro and in vivo methods, such as computational modelling, cell-based assays, animal studies, and clinical trials.

Two databases, ADMETlab 2.0 and ProTox-II, have been used to study toxicity. ADMETlab 2.0 (https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/) is an enhanced version of the widely used ADMETlab for systematical evaluation of ADMET properties, as well as some physicochemical properties and medicinal chemistry friendliness. ProTox-II (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/) is a virtual lab for the prediction of toxicities of small molecules.

Results

Molecular Docking

After performing successive dockings to investigate the binding tendency of plant compounds to the receptor, the obtained results were depicted in a tabular form. Two molecules Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) and Glycerol (GOL) were studied as control cases. The energy levels were equal to -161.109 and -52.7023 and the amino acids involved were Ser46(C), Tyr47(C), Glu133(A), Arg131(A), Ser88(C), Gln130(A), Leu132(A), and Tyr141(D). The available data showed that N-Vanillyloctanamide, a derivative of the ginger plant, had the lowest (most negative) energy level and the highest number of common amino acids with the main protein in the active site. Its energy level was -124.782.The available data showed that the compound, N-Vanillyloctanamide with energy levels of -124.782, a derivative of the ginger plant has the lowest (most negative) amount of energy with the highest number of common amino acids with the main protein in the active site. Table 1 shows the results of molecular docking with MVD software. In this table, the results of molecular docking between 3qdl protein and 32 similar compounds related to myristicin, and 18 similar compounds related to shogaol are given. In this table, the zinc code of each compound, the energy obtained from docking (mol dock score), and the number of amino acids in the binding site are given. Table 2 shows the results of molecular docking with Igemdock software. In this table, the results of molecular docking between 3qdl protein and 32 similar compounds related to myristicin, and 18 similar compounds related to shogaol are given. In this table, the zinc code of each compound, the total energy obtained from docking, the amount of van der Waals energy, H-BOND, and the number of amino acids in the binding site are given.

Table 1. Docking results with Molegro Virtual Docker.

Substance | ZINC ID | Mol dock score (kcal/mol) | Amino acids in binding sites |

M1 | 393470 | -102.789 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Glu133(A), Tyr141(D) |

M2 | 403089 | -100.121 | Tyr141(D), Gln130(A), Arg131(A) |

M3 | 2146907 | -92.6964 | Leu132(C), glu133(C), ser46(A), Gln139(A) |

M4 | 2529998 | -101.022 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Tyr141(D), Tyr47(C) |

M5 | 2566085 | -89.1359 | Tyr71(D), Lys181(A), Ile182(A) |

M6 | 2572638 | -99.8687 | Arg131(A), Leu132(A) |

M7 | 8727726 | -93.224 | Ser46(C), Tyr141(D), Gln130(A) |

M8 | 13495667 | -93.8757 | Leu132(A), Arg131(A) |

M9 | 14489946 | -104.402 | Arg132(A), Leu132(A), Gln139(C) |

M10 | 14489952 | -98.2083 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Tyr141(D), Tyr47(C) |

M11 | 14680083 | -96.8485 | Gln130(A), Tyr141(D), Arg131(A) |

M12 | 14818163 | -102.409 | Arg131(A), Leu132(A), Glu138(C) |

M13 | 14818165 | -100.36 | Tyr141(D), Gln130(A), Arg131(A), Glu133(A), Leu132(A) |

M14 | 22012904 | -102.445 | Leu132(A), Ser46(C), Met129(A) |

M15 | 22012908 | -101.446 | Arg131(A), Tyr141(D) |

M16 | 34182793 | -97.4565 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Tyr141(D) |

M17 | 34186837 | -95.9029 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Tyr141(D) |

M18 | 34186838 | -98.1223 | Leu132(C), Gln139(A) |

M19 | 38583412 | -95.3358 | Arg131(A), Leu132(A), Ser46(C)

|

M20 | 60249608 | -97.2704 | Tyr141(D), Gln130(A), Arg131(A) |

M21 | 65336712 | -102.6 | Leu132(C), Gln130(A), Arg131(C) |

M22 | 65336735 | -97.4431 | Tyr141(D), Gln130(A), Arg131(A) |

M23 | 95643541 | -102.58 | Tyr141(D), Gln130(A), Arg131(A) |

M24 | 95934481 | -99.9477 | Leu132(C), Ser46(C), Phe146(B), Gly162(B) |

M25 | 108374024 | -100.203 | Tyr141(D), Ala183(D), Ser46(C) |

M26 | 136922029 | -97.3492 | Arg131(A), Glu138(c), Leu132(A), Ser46(C) |

M27 | 222557475 | -103.14 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Tyr141(D), Tyr47(C) |

M28 | 229338797 | -89.1943 | Arg131(A), Tyr141(D), Tyr47(C) |

M29 | 229338955 | -97.6973 | Glu133(C), Gln133(C), Ser46(C), Arg131(C), Gln139(A), Glu138(A) |

M30 | 254568094 | -101.274 | Leu132(A), Arg131(A), Gln139(C) |

M31 | 257957021

| -106.576 | Arg131(A), Gln130(A), Tyr141(D), Glu133(A) |

M32 | 1690107322 | -92.96.85 | Tyr141(D), Gln130(A), Arg131(A) |

Sh1 | 1531857 | -121.701 | Ser88(D), Gln130(A) |

Sh2 | 1531865 | -127.035 | Gln138(A), Leu132(C), Arg131(C) |

Sh3 | 1627290 | -118.008 | Ser88(D), Tyr141(D), Arg131(A) |

Sh4 | 13887692 | -124.437 | Tyr47(C), Ser46(C), Ser45(C) |

Sh5 | 14708427 | -125.739 | Tyr141(D) |

Sh6 | 14708433 | -120.337 | Tyr47(A), Leu132(C) |

Sh7 | 43284710 | -124.782 | Leu132(C), Arg131(C) |

Sh8 | 58548705 | -122.083 | Tyr47(C), Glu138(C) , Leu132(A) , Arg131(A) |

Sh9 | 76289028 | -122.392 | Ser88(D), Lys181(D) |

Sh10 | 95099320 | -134.189 | Ser88(D), Gln130(A) |

Sh11 | 100294788 | -128.878 | Ile160(D), Ser46(C) |

Sh12 | 199628214 | -118.997 | Gln130(A), Leu132(A), Tyr47(C) |

Sh13 | 238744085 | -118.24 | Glu133(C), Gln139(A) |

Sh14 | 238751661 | -123.328 | Ile182(D), Leu132(A) |

Sh15 | 238760798 | -137.115 | Tyr47(A) |

Sh16 | 238777994 | -122.739 | Gly162(D), Leu132(A) |

Sh17 | 238789702 | -114.974 | Ser46(C) |

Sh18 | 238789703 | -131.987 | Ile182(D), Leu132(A) |

Table 2. Docking results with IGEMDOCK.

Substance | ZINC ID | Total energy (kcal/mol) | VAN DER WAALS energy (VDW) | H-BOND | Amino acids in binding sites

|

M1 | 393470 | -77.5122 | -63.5135 | -13.9987 | Ile160, Ser45, Ser46, Ile161, Gly162 |

M2 | 403089 | -76.77 | -66.1 | -10.67 | Ser45, Ser46, Gln139, Ile160, Pro44 |

M3 | 2146907 | -74.71 | -45.46 | -29.25 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys198, Arg200, Ser45, Asn48 |

M4 | 2529998 | -83.32 | -59.24 | -24.08 | Ser18, Ile160, Gly162, Tyr47, Ile161, Ser45, Ser46 |

M5 | 2566085 | -74.17 | -66.2 | -7.97 | Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Ser45, Gln139 |

M6 | 2572638 | -73.83 | -79.46 | -3.37 | Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gln139 |

M7 | 8727726 | -77.91 | -45.43 | -32.48 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys198, Arg200, Ser45, Asn48 |

M8 | 13495667 | -83.66 | -57.33 | -26.33 | Ser196, Gln197, Lys198, Arg200, Ser18, Asn48 |

M9 | 14489946 | -80.37 | -66.92 | -13.45 | Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Gln139, Ile160, Ile161 |

M10 | 14489952 | -73 | -58.58 | -14.42 | Ser18, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47 |

M11 | 14680083 | -76.32 | -65.72 | -10.6 | Tyr141, Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gln139 |

M12 | 14818163 | -86.22 | -68.69 | -17.52 | Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Gln139, Ile160, Ile161 |

M13 | 14818165 | -83.37 | -68.55 | -14.82 | Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Tyr47 |

M14 | 22012904 | -82.48 | -45.17 | -35.31 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys198, Arg200, His17 |

M15 | 22012908 | -75.43 | -64.05 | -10.49 | Gly162, Gly163, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47 |

M16 | 34182793 | -70.98 | -59.4 | -11.58 | Arg16, Ser18, Ser196, Arg200, His17, Lys198 |

M17 | 34186837 | -72.02 | -49.25 | -22.77 | Arg16, Ser18, Ser196, Lys198, Arg200, His17, Gln197, Ser199, Asn48 |

M18 | 34186838 | -80.71 | -61.4 | -19.31 | Ser18, Cys159, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45, Ser46 |

M19 | 38583412 | -69.81 | -60.65 | -9.16 | Ser45, Ser46, Ile160 |

M20 | 60249608 | -74.78 | -65.85 | -8.93 | Ser46, Gln139, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45 |

M21 | 65336712 | -79.8 | -53.49 | -26.31 | Gly162, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45 |

M22 | 65336735 | -77.29 | -52.13 | -25.16 | Arg16, Ser18, Ser199, Arg200, Gln197, Lys198 |

M23 | 95643541 | -83.64 | -69.67 | -13.97 | Ser18, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Ser45, Ser46 |

M24 | 95934481 | -85.83 | -61.94 | -23.89 | Ser18, Cys159, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45, Ser46, Gln139 |

M25 | 108374024 | -77.18 | -67.79 | -9.39 | Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gln139 |

M26 | 136922029 | -75.14 | -48.2 | -26.94 | Arg16, Ser18, Arg200, Asn48, Ser45, Tyr47 |

M27 | 222557475 | -79.65 | -64.38 | -15.27 | Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47, Gln139 |

M28 | 229338797 | -73.18 | -51.7 | -21.47 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys198, Arg200, Asn48 |

M29 | 229338955 | -88.73 | -60.98 | -27.75 | Gly162, Gly163, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47, Gln139 |

M30 | 254568094 | -82.54 | -61.41 | -21.13 | Tyr141, Gly162, Ala183, Ser46, Ser134, Ile160, Ile161 |

M31 | 257957021 | -82.62 | -65.22 | -17.4 | Gly162, Gly163, Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gln139 |

M32 | 1690107322 | -77.04 | -49.7 | -27.35 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys198, Arg200, His17, Gln197 |

Sh1 | 1531857 | -97.05 | -72.19 | -24.48 | Arg16, Arg200, Tyr47, Asn48, Ser18, Ile160, Ser45, Ser46 |

Sh2 | 1531865 | -97.18 | -83.6 | -13.58 | Asn73, Gly163, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Tyr47 |

Sh3 | 1627290 | -104.03 | -81.87 | -22.16 | Ser45, Ser46, Gly162, Tyr47, Asn48, Gln139, Ser18, Ile160, Ile161, Arg200 |

Sh4 | 13887692 | -99.98 | -80.63 | -19.35 | Arg16, Lys198, Arg200, Ser18, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47, Asn48 |

Sh5 | 14708427 | -94.15 | -80.33 | -13.82 | Gly162, Gly163, Asn48, Ser18, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47 |

Sh6 | 14708433 | -98.24 | -86.89 | -11.36 | Ser45, Ser46, Gln139, Ile160, Ile161, Pro44, Tyr47 |

Sh7 | 43284710 | -98.01 | -80.01 | -18 | Asn73, Gly162, Gly163, Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Arg200, Pro44 |

Sh8 | 58548705 | -100.08

| -85.14 | -14.94 | Ser18, Ser46, Gln139, Ile160, Pro44, Ser45 |

Sh9 | 76289028 | -90.03 | -66.95 | -23.09 | Arg16, Ser18, Ile160, Lys198, Arg200, Pro44, Ser46, Tyr47 |

Sh10 | 95099320 | -96.67 | -83.36 | -13.31 | Arg200, Ser46, Tyr47, Ser18, Ile160, Lys198, Pro44, Ser45, Asn48 |

Sh11 | 100294788 | -96.06 | -86.02 | -10.04 | Ser18, Gly162, Tyr47, Ile160, Pro44, Ser45, Ser46, Asn48 |

Sh12 | 199628214 | -96.22 | -84.64 | -11.88 | Asn73, Gly162, Gly163, Tyr141, Ile160, Ile161, Ser46, Tyr47, Gln139 |

Sh13 | 238744085 | -91.17 | -88.42 | -2.74 | Tyr47, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Ser45, Ser46, Gln139 |

Sh14 | 238751661 | -96.89 | -89.89 | -7 | Gly162, Tyr47, Ile160, Lys198, Arg200, Ser45, Ser46 |

Sh15 | 238760798 | -96.01 | -76.2 | -19.81 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys20, Lys198, Arg200, Ser45, Ser46, Tyr47 |

Sh16 | 238777994 | -92.37 | -84.28 | -8.09 | Ser18, Gly162, Ile160, Ile161, Ser45, Ser46, Gln139 |

Sh17 | 238789702 | -92.73 | -79.59 | -13.14 | Ser46, Ser134, Gln139, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Ser45 |

Sh18 | 238789703 | -99.74 | -79.11 | -20.64 | Arg16, Ser18, Lys20, Lys198, Arg200, Ile160, Ser45, Ser46 |

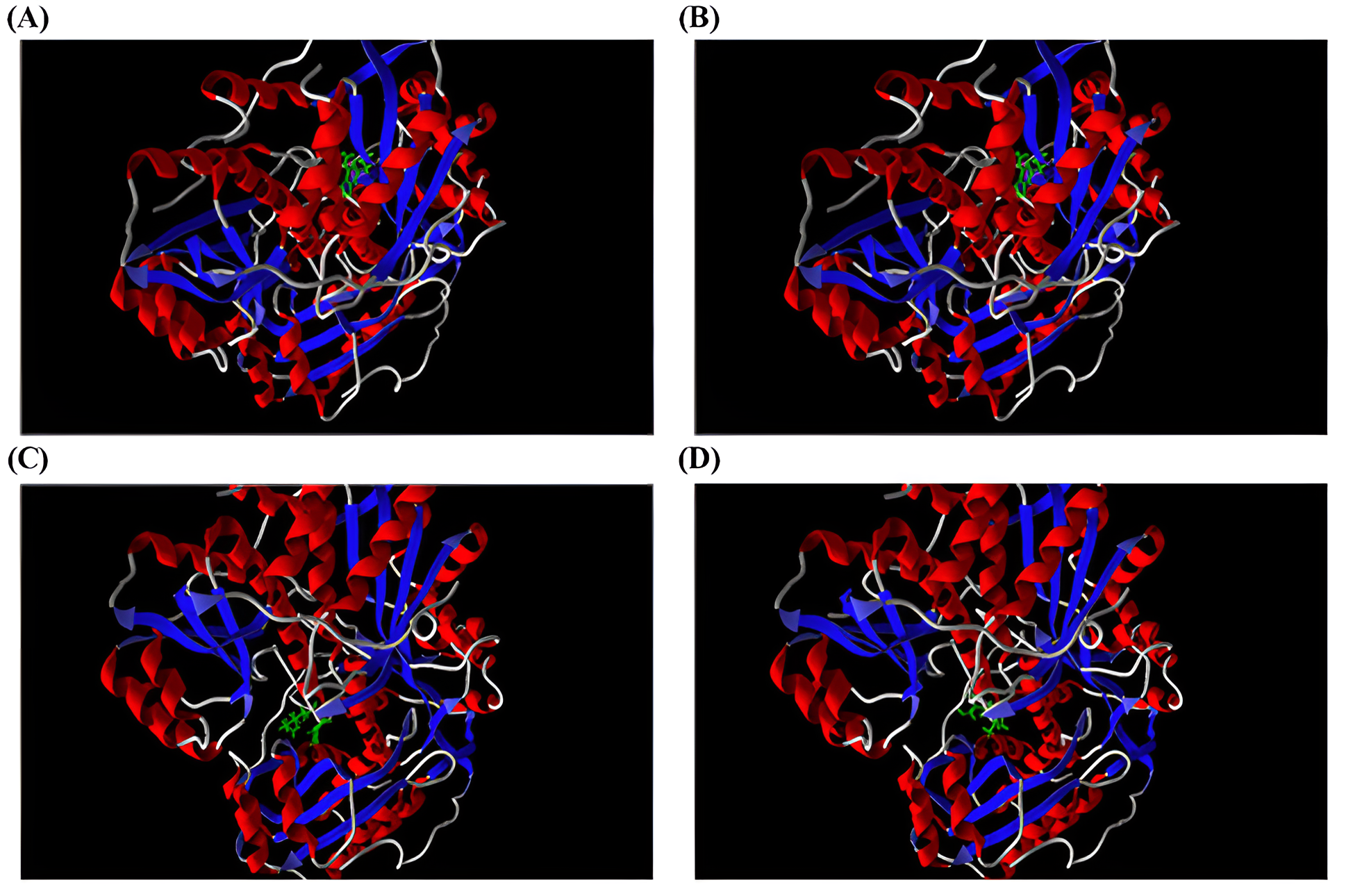

The BIOVIA Discovery Studio software was used to find amino acids in binding sites of 3qdl protein. The amino acids in binding sites of this protein in all four chains A, B, C, and D were as follows: Arg16, His17, Ser18, Lys20, Glu34, Pro44, Ser45, Ser46, Asn48, Asn73, Ile142, Cys159, Ile160, Ile161, Gly162, Gly163, Lys198, and Arg200. The results of docking were examined in two dimensions. The first dimension is in terms of the energy of each ligand and the second dimension is in terms of the amino acids in the binding sites of each ligand.Among the results of molecular docking with MVD software, out of 50 molecules, Myristicin, with a zinc code of 25795702 and a MolDock score of -106.567, and Shogaol, with a zinc code of 238760798 and a total energy of -137.115, had the lowest energy levels (the most negative). Similarly, among the results of molecular docking with iGemdock software, Myristicin, with a zinc code of 229338955 and a total energy of -88.73, and Shogaol, with a zinc code of 1627290 and a total energy of -104.03, had the lowest energy levels (the most negative).

According to the results of BIOVIA Discovery Studio software and molecular docking with MVD, Ligand software with zinc code equal to 95934481 related to Myristicin with two common amino acids in binding sites with the main protein which were Ser46(c) and Gly162(b) and the ligand with zinc code equal to 100294788 related to Shogaol substance with two common amino acids in binding sites with the main protein which were Ser46(c) and Ile160(d) were selected. According to the results of BIOVIA Discovery Studio software and molecular docking with Igemdock software, the ligand with zinc code equal to 257957021 related to Myristicin substance with six amino acids in binding sites in common with the main protein, which were Ser45(c) Gly163, ser46, Ile160, Ile161, and Gly162 and the ligand with zinc code equal to 43284710 related to Shogaol substance with nine common amino acids in binding sites with the main protein which were Ser45, Ser46, Ile160, Ile161, Gly163, Asn73, Arg200, Pro44, and Gly162 were selected. In cases where the number of common amino acids in binding sites of two or more zinc codes was equal, the code with the lowest energy (the most negative) was selected.

The result of docking with MVD software was that the mol dock score was equal to -85.1506 and the number of common amino acids in binding sites with the output of Biovia software was equal to one active site, which was Ser46(c). The result of docking with iGemdock software was that the total energy was equal to -87.9 and the number of common amino acids in binding sites with the output of Biovia software was equal to four active sites, which were: Arg16, Lys198, Ser18, Arg200. Among the tested phytocompounds, no phytochemical was able to outperform the control in terms of binding energy. Therefore, considering the importance of the active site residues, this dimension was prioritized.

Figure 1. 3D structure of 3qdl and its ligands.

Figure 2. Docking result for 4 best molecules with MVD (A) ZINC ID: 95934481, (B) ZINC ID: 100294788, (C) ZINC ID: 257957021, and (D) ZINC ID: 43284710.

Method Validation

The RMSD values for the predicted and reference structures were calculated using the superimposition of the native ligand and receptor. The RMSD values for each protein were compared with a main protein value of 2.543. The results were as follows:

- Protein a: RMSD = 3.00

- Protein b: RMSD = 1.00

- Protein c: RMSD = 0.10

- Protein d: RMSD = 3.4

Based on these values, it was observed that protein C had the lowest RMSD value, indicating that it was the most similar to the main protein. Protein A and protein B had relatively low RMSD values, indicating that they were also somewhat similar to the main protein. Protein d had the highest RMSD value, indicating that it was the most different from the main protein. Overall, the differences between the proteins were relatively small, as the highest RMSD value was only 3.4 (compared to 2.543 for the main protein). However, the interpretation of these values depended on the context of the analysis and the specific goals of the research. Smaller RMSD value indicated that the ligand had bonded more with the active site amino acids.

Table 3. Toxicity studies using the ADMETlab website for four selected molecules.

Zinc ID | hERG Blockers | H-HT | DILI | AMES Toxicity@ | Rat Oral Acute Toxicity | FDAMDD* | Skin Sensitization | Carcinogencity | Eye Corrosion | Eye irritation | Respiratory Toxicity |

95934481 | .031 | .806 | 0.148 | 0.522 | 0.454 | 0.656 | 0.512 | 0.932 | 0.83 | 0.067 | 0.93 |

25757021 | 0.017 | 0.321 | 0.177 | 0.041 | 0.019 | 0.635 | 0.682 | 0.887 | 0.019 | 0.755 | 0.084 |

100294788 | 0.065 | 0.422 | 0.432 | 0.159 | 0.587 | 0.21 | 0.953 | 0.598 | 0.159 | 0.962 | 0956 |

43284710 | 0.159 | 0.09 | 0.054 | 0.075 | 0.041 | 0.029 | 0.844 | 0.045 | 0.006 | 0.088 | 0.074 |

Note: *The maximum recommended daily dose provides an estimate of the toxic dose threshold of chemicals in humans. @The test for mutagenicity. hERG = human ether-a-go-go related gene; DILI = drug-induced liver injury; H-HT = human hepatotoxicity. | |||||||||||

Table 4. Toxicity studies using the ProTox-II website for four selected molecules.

Predicted toxicity class | LD50 (mg/kg) | Zinc ID |

3 | 170 | 95934481 |

4 | 1000 | 257957021 |

4 | 1250 | 43284710 |

5 | 2300 | 100294788 |

Note: Class I: fatal if swallowed (LD50 ≤ 5); Class II: fatal if swallowed (5 < LD50 ≤ 50); Class III: toxic if swallowed (50 < LD50 ≤ 300); Class IV: harmful if swallowed (300 < LD50 ≤ 2000); Class V: may be harmful if swallowed (2000 < LD50 ≤ 5000); and Class VI: non-toxic (LD50 > 5000). | ||

Toxicity Studies

The in silico toxicity studies with the ADMETlab and ProTox-II tools are given in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. The study indicates that all the phytocompounds have an LD50 higher than 170 mg/kg body weight and might be toxic if ingested above the recommended LD50. According to Table 3 and 4, which is related to toxicity studies, the four phytocompounds might show signs of toxicity. However, the in silico results are based on a model that is trained from a group of compounds with known toxicity, and hence, the in silico results might not be completely accurate due to differences in the chemical structures of the training sets and the test sets.

Discussion

N-Vanillyloctanamide compound, which was derived from the ginger plant and Shogaol substance, had inhibitory effects against the 3qdl protein of H. pylori bacteria, which indicates that plant compounds can be introduced as a potential antibiotic. O’Mahony et al. (2005), Ebrahimzadeh Attari et al. (2019) and Hedieh Yousef-Nezhad et al. (2017) proved that parsley and ginger showed inhibitory activity against H. pylori (17-19). Weerasekera et al. (2008) confirmed in a study that parsley has bactericidal properties, but the complete inhibition of bacteria was not achieved in 60 minutes (20). Another study assessed the effects of curcumin, a polyphenolic compound found in turmeric, on the Oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme of H. pylori. The study reported that curcumin inhibited the enzyme's activity, reduced H. pylori growth, and increased metronidazole sensitivity in H. pylori strains resistant to the antibiotic (21). Ebrahimzadeh Attari et al. (2019) concluded that ginger can be considered a useful complementary therapy for functional dyspepsia (22). Azadi et al. (2019) showed that a combination of cinnamon and ginger extracts can have inhibitory effects against H. pylori (23). Sistani Karampour et al. (2019) showed that ginger can have protective effects on gastric ulcers (24). Al Yahya et al. (1989) showed that ginger has cytoprotective and anti-ulcerogenic effects (25).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of this study provide promising insights into the development of new treatment strategies for H. pylori infections, especially in cases where antibiotic resistance occurs, and suggest that targeting the Oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme may be a promising approach for the development of new and more effective drugs for the treatment of H. pylori infections. Our study demonstrated that ginger might have an inhibitory effect on the oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitro reductase enzyme of H. pylori strains that are resistant to metronidazole. Among the tested phytocompounds, no phytochemical was able to outperform the control in terms of binding energy. Therefore, considering the importance of the active site residues, this factor was prioritized for choosing phytocompounds with potential activity. Further studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these compounds and to investigate their potential use in combination with other antibiotics to enhance their antimicrobial activity against H. pylori.

Declarations

Acknowledgment

We appreciate and thank all the people and organizations who helped us in writing this article.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability

The unpublished data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Funding Information

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicting interest.

References

- Talebi Bazmin Abadi A, Mohabati Mobarez A, Ajami A, Rafiei A, Taghvaei T. Investigating the antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Patients referred to Tubi Sari Medical Complex. J Maz Univ Med. (2009) 19:26-32.

- Krzyżek P, Gościniak G. Morphology of Helicobacter pylori as a result of peptidoglycan and cytoskeleton rearrangements. Prz Gastroenterol. (2018) 13(3):182-95.

- Bakhshi S, Ghazvini K, Beheshti A, Ahadi M, Sheykhi M. Review of antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Iran and the world. Med J Mashhad Univ Med Sci. (2017) 60:648-61.

- Kao CY, Sheu BS, Wu JJ. Helicobacter pylori infection: An overview of bacterial virulence factors and pathogenesis. Biomed J. (2016) 39(1):14-23.

- Antimicrobial resistance. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/antimicrobial-resistance. Accessed: 27 November 2022.

- Kaboli SA, Garmrudi B, Roshanaei G, Majlesi A, Khalilian A, Aghajanimir MS. Comparison of Sequential Regimen and Standard Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Patients with Dyspepsia. Avicenna J Clin Med. (2013) 20(3):184-93.

- Savoldi A, Carrara E, Graham DY, Conti M, Tacconelli E. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis in World Health Organization Regions. Gastroenterol. (2018) 155(5):1372-82.

- Jenks PJ, Edwards DI. Metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2002) 19:1-7.

- Safaei H, Mirzaei N, Poursina F, Moghim S, Rahimi E. The mutation of the rdxA gene in metronidazole-resistant Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. Adv Biomed Res. (2014) 3:90.

- Aali E, Mahmoudi R, Kazeminia M, Hazrati R, Azarpey F. Plant essential oils as natural medicinal compounds: a review article. Tehran Univ Med J. (2017) 7:480-9.

- Ekins S, Mestres J, Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: methods for virtual ligand screening and profiling. Br J Pharmacol. (2007) 152(1):9-20.

- Sarve Ahrabi Y. Anti-Helicobacter pylori Activity of New Derivatives of 1, 3, 4-Oxadiazole: In Silico Study. Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect. (2021) 8:135-8.

- FazeliNasab B. In Silico Analysis of the Effect of Scrophularia striata Linalool on VacA Protein of Helicobacter Pylori. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. (2021) 29:50-64.

- Divyashri G, Krishna Murthy TP, Sundareshan S, Kamath P, Murahari M, Saraswathy GR, Sadanandan B. In silico approach towards the identification of potential inhibitors from Curcuma amada Roxb against H. pylori: ADMET screening and molecular docking studies. Bioimpacts. (2021) 11(2):119-27.

- Thomsen R, Christensen MH. MolDock: a new technique for high-accuracy molecular docking. J Med Chem. (2006) 49(11):3315-21.

- Hsu KC, Chen YF, Lin SR, Yang JM. iGEMDOCK: a graphical environment of enhancing GEMDOCK using pharmacological interactions and post-screening analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. (2011) 12:1-1.

- O'Mahony R, Al-Khtheeri H, Weerasekera D, Fernando N, Vaira D, Holton J, Basset C. Bactericidal and anti-adhesive properties of culinary and medicinal plants against Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. (2005) 11(47):7499-507.

- Ebrahimzadeh Attari V, Somi MH, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Ostadrahimi A, Moaddab SY, Lotfi N. The Gastro-protective Effect of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) in Helicobacter pylori Positive Functional Dyspepsia. Adv Pharm Bull. (2019) 9(2):321-4.

- Yousef-Nezhad, H., Hejazi, N. Anti-Bacterial Properties of Herbs against Helicobacter Pylori Infection: A Review. Int J Nutrit Sci. (2017) 2(3): 126-33.

- Weerasekera D, Fernando N, Bogahawatta LB, Rajapakse-Mallikahewa R, Naulla DJ. Bactericidal effect of selected spices, medicinal plants and tea on Helicobacter pylori strains from Sri Lanka. J National Sci Found. (2008) 36(1):91-4.

- Tsai YM, Chien CF, Lin LC, Tsai TH. Curcumin and its nano-formulation: the kinetics of tissue distribution and blood–brain barrier penetration. Int J Pharm. (2011) 416(1):331-8.

- Ebrahimzadeh Attari V, Somi MH, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Ostadrahimi A, Moaddab SY, Lotfi N. The Gastro-protective Effect of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) in Helicobacter pylori Positive Functional Dyspepsia. Adv Pharm Bull. (2019) 9(2):321-4.

- Azadi M, Ebrahimi A, Khaledi A, Esmaeili D. Study of inhibitory effects of the mixture of cinnamon and ginger extracts on cagA gene expression of Helicobacter pylori by Real-Time RT-PCR technique. Gene Rep. (2019) 17:100493.

- Sistani Karampour N, Arzi A, Rezaie A, Pashmforoosh M, Kordi F. Gastroprotective effect of zingerone on ethanol-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Medicina. (2019) 55(3):64.

- Al-Yahya MA, Rafatullah S, Mossa JS, Ageel AM, Parmar NS, Tariq M. Gastroprotective activity of ginger zingiber officinale rosc., in albino rats. Am J Chin Med. (1989) 17(1-2):51-6.

ETFLIN

Notification

ETFLIN

Notification