Could Ginger Extract Be a Therapeutic Drug for Migraine?

Academic editor: James H. Zothantluanga

Sciences of Phytochemistry 2(1): 60-65 (2023); https://doi.org/10.58920/sciphy02010075

This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International License.

14 Apr 2023

30 Apr 2023

12 May 2023

12 May 2023

Abstract: Migraine is a common neurological disorder that may be accompanied by vascular disturbances, Migraine is one of the most causes of disability worldwide. Zingiber officinale is a medicinal herb that has an analgesic effect on many disorders such as headaches, migraine, muscle tension, stomach spasm, and dysmenorrhea. Also, ginger has many pharmacological actions used to treat and prevent various common symptoms and diseases. This review aims to evaluate the potential of ginger to treat or prevent migraine episodes. Especially nowadays, patients prefer herbal and complementary medicine to avoid the hard side effects of chemical drugs. The author searched several databases including PubMed, Science Direct, Wiley Online, and Scopus through February 2023 for recent articles with good quality evaluating the potential of ginger to treat migraine patients. The author made investigations and Interpretations depending on the results of the authors' experiments in previous articles included in my review. It is suggested that the bioactive compounds in ginger have the potential to treat and prevent acute migraine episodes effectively and safely. The author recommends encouraging the manufacturing of different pharmaceutical dosage forms of ginger extract to be used worldwide in a safe way and to render a higher absorption rate, and pharmacological response.

Keywords: GingerHeadacheKetoprofenMigraineSumatriptanZingiber officinale

Introduction

Migraine is considered a neurological disorder. It may be accompanied by visual, gastrointestinal, and/or premenstrual disturbances (1). It is a significant contributor to disability and lowers people's quality of life globally (2-6). According to estimates, migraines cause 45 million years of impairment to be lived globally, with a prevalence of 8 to 18% (7-14). Prophylaxis and effective treatment can decrease migraine attacks’ severity and frequency (15). There are several classes of drugs commonly used for migraine treatment, such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, anti-epileptic drugs, triptans, ergot alkaloids, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may cause various side effects and are prescribed with caution for a limited duration (16). Due to their unhappiness with traditional therapy and associated adverse effects, many patients prefer nonchemical (herbal) or easily accessible over-the-counter (OTC) medications to treat their headaches (17, 18). Southeast Asia is home to the popular medicinal plant ginger. Dehydrated zingiber rhizomes include 40–60% carbohydrates, 10% protein, 10% fat, 5% fibre, 6% minerals, 10% water, 1% essential oil, and 5%–8% resin and mucilage (19-21). The volatile and non-volatile compounds found in ginger rhizomes are numerous. The ginger's flavour comes from volatile compounds, which make up a small portion of the ginger rhizome. The primary bioactive compounds are non-volatile, which include shogaols and gingerols. These bioactive compounds can be found in ginger extracts (22). Ginger has analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects so that it could relieve pain (23, 24).

Ginger Effects on Migraine Patients

Administration of 400 mg of ginger extract greatly reduced pain in acute migraine patients (25). In a previous study performed by Cady et al. (2005) Gelstat (an OTC drug that contains ginger extract) improved migraine headaches within 2 hours of administration of the drug (26). In a previous case report, a 42-year-old woman with a 16-year history of migraine achieved headache relief within 30 minutes of administration of a 500–600 mg water-soluble ginger powder till the onset of visual aura. Patients, who continued consumption of ginger powder, every 4 hours for four days, reported both diminished headache severity and frequency (21). A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 100) comparing the efficacy of ginger and sumatriptan in treating migraine without aura found the 2 agents equally effective. Patients who took sumatriptan (50 mg) or ginger (250 mg ginger rhizome powder) within two hours of taking it reported at least a 90% reduction in headache intensity (27). In a randomized controlled trial, patients taking a sublingual product containing feverfew (another medicinal herb) and ginger at the earliest recognition of migraine twice daily were free of pain at two hours compared to patients taking a placebo (P = .02) (28). Patients who reported migraine episodes and administered 400 mg of ginger extract divided into two capsules (containing 20 mg (5%) of active gingerols), and an intravenous drug of 100 mg ketoprofen resulted in a pain decrease and the functional capacity was improved (29). Administration of 500 mg of ginger powder three times a day for 2 days before the onset of the menstrual period and continued for the first three days of the menstrual period was reported to be effective to decrease the severity of dysmenorrhea-related pain (30). Chen & Cai. (2021) have confirmed the effect of ginger to reduce migraine-induced nausea and vomiting. Ginger showed antiemetic properties and improved nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy, post-operative, or during pregnancy (30-34). Ginger has a lot of pharmacological actions that greatly contribute to the improvement of migraine symptoms.

Methodology for Review

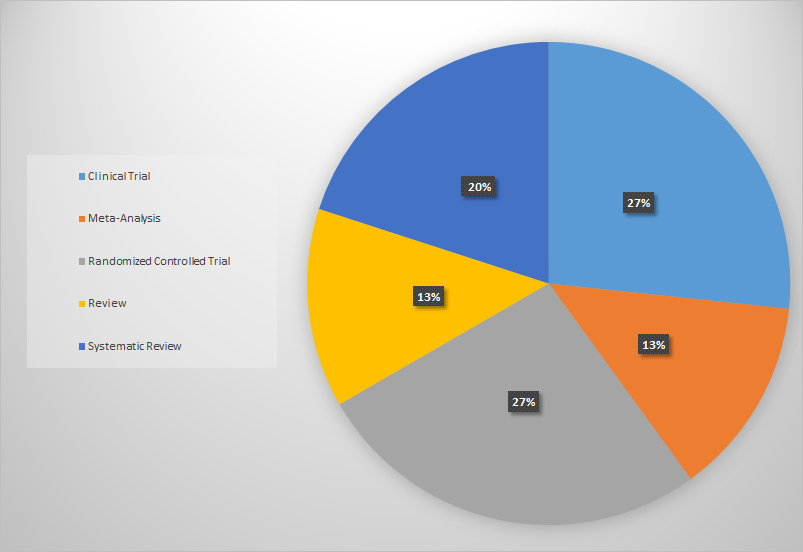

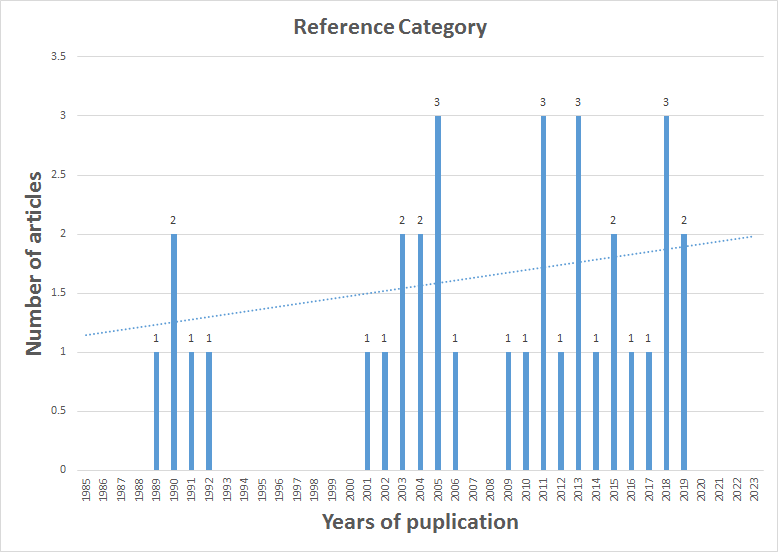

The author searched a lot of databases including PubMed, Wiley Online, Scopus, and Science Direct through February 2023 for articles with good quality evaluating the potential of ginger in the treatment of migraine patients with the following keywords: “migraine”, and “ginger” or “Zingiber” (see Figure 1). The reference lists of papers were also hand-searched, and the author has performed the process above repeatedly to include additional better studies. He made investigations and Interpretations depending on the results of the authors' experiments in previous articles included in my review. Finally, He has used Microsoft Office Excel software to design the following charts that classify the number and type of included articles each year. It is noted that there are few clinical trials and randomized controlled studies evaluating the potential of ginger for treating migraine, however, we can see a kind of evolution of research in this field compared to the past (see Figure 1 and 2).

Effect of Ginger Extract on Biomarkers

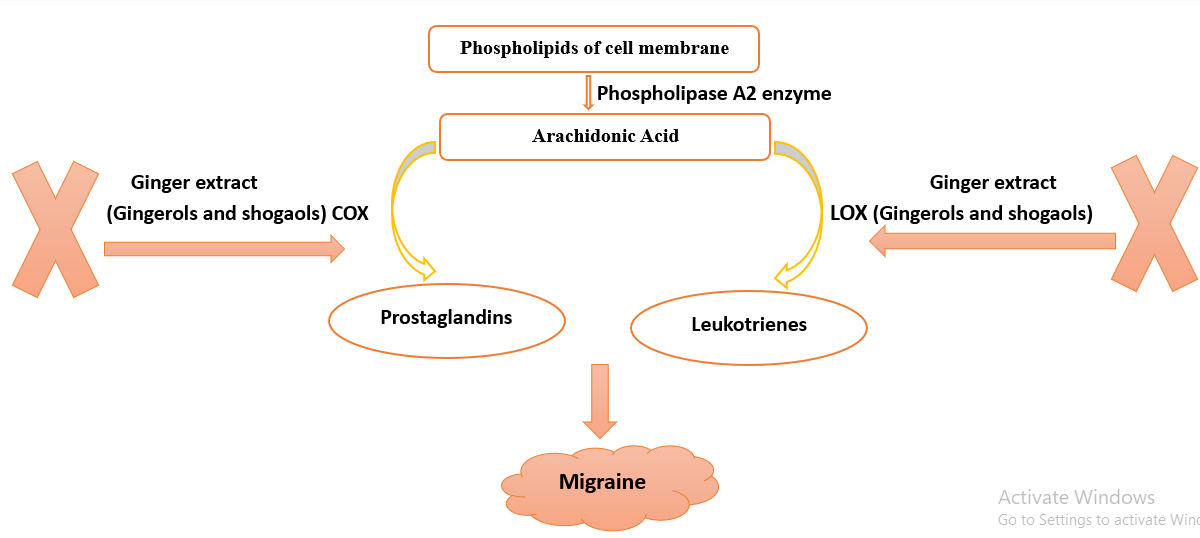

The release of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, cytokines, and bradykinin due to the release of neuropeptides that activate trigeminal nerve fibers activate nociceptive pathways during migraine attacks (35, 36). Drugs used in pain treatment usually act by altering the transduction and/or modulation of nociception (37). Symptoms associated with migraine attacks can be activated by nociceptive signals, therefore, the blocking of nociceptive pathways may improve these symptoms (38). The analgesic action of ginger is due to its active components; gingerols and shogaols that inhibit arachidonic acid metabolism via decreasing the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme (COX-2), leading to inhibition of prostaglandin biosynthesis like the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (39, 40). Ginger blocks lipoxygenase (LOX), another enzyme in the arachidonic acid pathway (41). The concomitant inhibition of COX and LOX may increase anti-inflammatory action and reduce its side effects (42).

Figure 1. Types of collected articles only evaluate the potential of ginger to treat migraine.

Figure 2. The included studies' distribution only evaluates ginger's potential to treat migraine each year.

Figure 3. Ginger extract role in the treatment of migraine episodes.

Furthermore, shogaols modulate neuroinflammatory pathways via the downregulation of inflammatory spots on existing microglial cells that regulate brain development, maintenance of neuronal networks, and injury repair and serve as brain macrophages as they are responsible for the elimination of microbes, dead cells, redundant synapses, protein aggregates, and other particulate and soluble antigens that may endanger the CNS (43). While gingerols may act as agonists of the capsaicin-activated vanilloid receptors that evoke capsaicin-like intracellular Ca2+ transients and ion currents (44). All these various mechanisms of ginger render more benefits to improve migraine (Figure 3).

Conclusions

Considering the above, powdered, or fresh ginger has the potential to treat acute migraine patients, but with some limitations (45). Using ginger as an add-on therapy to NSAIDs renders more benefits not only for treatment but also for prophylaxis (29). It is suggested that 250 mg of ginger rhizome powder is clinically effective and safe to treat migraine headaches (27). In patients administering ginger, some side effects were observed such as heartburn, headaches, and vertigo, especially if taken in large doses (46, 47). The author pays attention that ginger should not be used as a replacement for prescribed medication without consulting a healthcare professional.

Declarations

Acknowledgment

There is a lot I need to thank God for, every day. But I think I am blessed because I have a very loving, understanding and supporting family. The author is grateful to his mother, Mona, his father, Abd El-Moniem, his brothers, Mohamed, Mahmoud, and Omar, his sister, Menna, and his best friends. The author expresses his gratitude to all his professors and teachers. The author declares that there are some limitations as the appropriate dose, and pharmaceutical dosage form of ginger for treating migraine needs to be established through well-designed clinical trials on a large scale for relatively long follow-up periods to determine the optimal dosage, duration of treatment, and potential side effects of ginger in treating migraine.

Ethics Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability

The unpublished data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Funding Information

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflicting interest.

References

- Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of migraine. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. (2012) 15 (1):15-22.

- Charles A. The pathophysiology of migraine: implications for clinical management. Lancet Neurol. (2018)17(2):174-182.

- Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet. (2018) 391(10127):1315-1330.

- Minen MT, Begasse De Dhaem O, Kroon Van Diest A, Powers S, Schwedt TJ, Lipton R, Silbersweig D. Migraine, and its psychiatric comorbidities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2016) 87(7):741-9.

- Burch R. Migraine and Tension-Type Headache: Diagnosis and Treatment. Med Clin North Am. (2019) 103(2):215-233.

- Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J. Epidemiology of headache in a general population--a prevalence study. J Clin Epidemiol. (1991) 44(11):1147-1157.

- Rasmussen BK. Epidemiology of headache. Cephalalgia. (2001) 21(7):774–777.

- Ascaso FJ, Marco S, Mateo J, Martínez M, Esteban O, Grzybowski A. Optical Coherence Tomography in Patients with Chronic Migraine: Literature Review and Update. Front Neurol. (2017) 8: 684.

- Radtke A, Neuhauser H. Prevalence and burden of headache and migraine in Germany. Headache. (2009) 49(1):79–89.

- Karli N, Zarifoğlu M, Ertafş M, Saip S, Oztürk V, Biçakçi S, Boz C, Selçuki D, Oğuzhanoğlu A, Neyal M, Siva A, Irkeç C, Kaleağasi H, Kansu T, Sarica Y, Taşdemir N, Uzuner N. Economic impact of primary headaches in Turkey: a university hospital-based study: part II. J Headache Pain. 2006;7(2):75-82.

- Falavigna A, Teles AR, Velho MC, Vedana VM, Silva RC, Mazzocchin T, Basso M, Braga GL. Prevalence, and impact of headache in undergraduate students in Southern Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2010) 68(6):873-877.

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Kolodner K, Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Steiner TJ. The family impact of migraine: population-based studies in the USA and UK. Cephalalgia. (2003) 23(6):429-440.

- Lipton RB, Liberman JN, Kolodner KB, Bigal ME, Dowson A, Stewart WF. Migraine headache disability and health-related quality-of-life: a population-based case-control study from England. Cephalalgia. (2003) 23(6):441-450.

- GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. (2018)17(11):954-976.

- MacGregor EA. Migraine. Ann Intern Med. (2017)166(7):49-64.

- VanderPluym JH, Halker Singh RB, Urtecho M, Morrow AS, Nayfeh T, Torres Roldan VD, Farah MH, Hasan B, Saadi S, Shah S, Abd-Rabu R, Daraz L, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Wang Z. Acute Treatments for Episodic Migraine in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. (2021) 325(23):2357-2369.

- Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A. Alternative headache treatments: nutraceuticals, behavioral and physical treatments. Headache. (2011) 51(3):469-483.

- Phutrakool P, Pongpirul K. Acceptance and use of complementary and alternative medicine among medical specialists: a 15-year systematic review and data synthesis. Syst Rev. (2022) 11(1):10.

- Lien HC, Sun WM, Chen YH, Kim H, Hasler W, Owyang C. Effects of ginger on motion sickness and gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias induced by circular vection. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2003) 284(3):481-489.

- Mascolo N, Jain R, Jain SC, Capasso F. Ethnopharmacologic investigation of ginger (Zingiber officinale). J Ethnopharmacol. (1989) 27(1-2):129-40.

- Mustafa T, Srivastava KC. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) in migraine headache. J Ethnopharmacol. (1990) 29(3):267-273.

- Rahmani AH, Shabrmi FM, Aly SM. Active ingredients of ginger as potential candidates in the prevention and treatment of diseases via modulation of biological activities. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. (2014) 6(2):125-36.

- Black CD, Oconnor PJ. Acute effects of dietary ginger on quadriceps muscle pain during moderate-intensity cycling exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2008) 18(6):653-664.

- Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med. (2009) 15(2):129-132.

- Chen L, Cai Z. The efficacy of ginger for the treatment of migraine: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Am J Emerg Med. (2021) 46: 567-571.

- Cady RK, Schreiber CP, Beach ME, Hart CC. Gelstat Migraine (sublingually administered feverfew and ginger compound) for acute treatment of migraine when administered during the mild pain phase. Med Sci Monit. (2005) 11(9):65-69.

- Maghbooli M, Golipour F, Moghimi Esfandabadi A, Yousefi M. Comparison between the efficacy of ginger and sumatriptan in the ablative treatment of the common migraine. Phytother Res. (2014) 28(3):412-415.

- Cady RK, Goldstein J, Nett R, Mitchell R, Beach ME, Browning R. A double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study of sublingual feverfew and ginger (LipiGesic™ M) in the treatment of migraine. Headache. (2011) 51(7):1078-1086.

- Martins LB, Rodrigues AMDS, Rodrigues DF, Dos Santos LC, Teixeira AL, Ferreira AVM. Double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) addition in migraine acute treatment. Cephalalgia. (2019) 39(1):68-76.

- Rahnama P, Montazeri A, Huseini HF, Kianbakht S, Naseri M. Effect of Zingiber officinale R. rhizomes (ginger) on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: a placebo randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2012) 12:92.

- Marx W, Ried K, McCarthy AL, Vitetta L, Sali A, McKavanagh D, Isenring L. Ginger-Mechanism of action in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2017) 57(1):141-146.

- Bryer E. A literature review of the effectiveness of ginger in alleviating mild-to-moderate nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2005) 50(1):1-3.

- Bode AM, Dong Z. (2011) Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects. In: The Amazing and Mighty Ginger, Editor: Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, 9781439807163, 2nd Edition.

- Bone ME, Wilkinson DJ, Young JR, McNeil J, Charlton S. Ginger root--a new antiemetic. The effect of ginger root on postoperative nausea and vomiting after major gynaecological surgery. Anaesthesia. (1990) 45(8):669-671.

- Schaible HG, Richter F. Pathophysiology of pain. Langenbecks Arch Surg. (2004) 389(4):237-243.

- Waeber C, Moskowitz MA. Migraine as an inflammatory disorder. Neurology. (2005) 64(10): 9-15.

- Babos MB, Grady B, Wisnoff W, McGhee C. Pathophysiology of pain. Dis Mon. (2013) 59(10):330-358.

- Noseda R, Burstein R. Migraine pathophysiology: anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, cortical spreading depression, sensitization, and modulation of pain. Pain. (2013)154(1):44-53.

- Grzanna R, Lindmark L, Frondoza CG. Ginger--an herbal medicinal product with broad anti-inflammatory actions. J Med Food. (2005) 8(2):125-132.

- Jolad SD, Lantz RC, Solyom AM, Chen GJ, Bates RB, Timmermann BN. Fresh organically grown ginger (Zingiber officinale): composition and effects on LPS-induced PGE2 production. Phytochemistry. (2004) 65(13):1937-1954.

- Kiuchi F, Iwakami S, Shibuya M, Hanaoka F, Sankawa U. Inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotriene biosynthesis by gingerols and diarylheptanoids. Chem Pharm Bull. (1992) 40(2):387-391.

- Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Reboul P, Pelletier JP. Therapeutic role of dual inhibitors of 5-LOX and COX, selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Rheum Dis. (2003) 62(6):501-509.

- Jackson JL, Cogbill E, Santana-Davila R, Eldredge C, Collier W, Gradall A, Sehgal N, Kuester J. A Comparative Effectiveness Meta-Analysis of Drugs for the Prophylaxis of Migraine Headache. PLoS One. (2015) 10(7):e0130733.

- Dedov VN, Tran VH, Duke CC, Connor M, Christie MJ, Mandadi S, Roufogalis BD. Gingerols: a novel class of vanilloid receptor (VR1) agonists. Br J Pharmacol. (2002) 137(6):793-798.

- Andrade C. Ginger for Migraine. J Clin Psychiatry. (2021) 82(6):21f14325.

- Novais C, Molina AK, Abreu RMV, Santo-Buelga C, Ferreira ICFR, Pereira C, Barros L. Natural Food Colorants and Preservatives: A Review, a Demand, and a Challenge. J Agric Food Chem. (2022) 70(9):2789-2805.

- Kim SD, Kwag EB, Yang MX, Yoo HS. Efficacy and Safety of Ginger on the Side Effects of Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(19):11267.

ETFLIN

Notification

ETFLIN

Notification